Introduction

In recent decades, long-term care in nursing homes has made a cultural shift from a medical environment toward a model in which care is provided in a more person-centered way (Koren, 2010). The principles of autonomy and shared decision-making are important. Residents should be involved in deciding how and when care is provided, activities are organized, and where and when to spend time with others (Blok et al., 2022; Koren, 2010; Tuominen et al., 2016). However, Agich (1990) emphasized that providing choices in activities, meals, and outings without knowing what the persons themselves perceive as valuable does not automatically lead to autonomy. Agich (1990) strongly advocated for knowing and working with residents’ values.

The framework for person-centered practice (PCP) mentions the principles of working with residents’ beliefs and values and sharing decision-making. These aspects are mentioned as processes underpinning PCP (McCormack & McCance, 2016). Mayer et al. (2020) further developed the PCP framework for nursing home care, adding fundamental principles of care to it; for example, “the resident should be free in decisions and should have an autonomous (…) lifestyle within the nursing home” (Mayer et al., 2020, p. 10). These principles also apply to older adults with physical impairments who live in nursing homes, which is the intended population for this study. Generally, these persons are able to make decisions about how they want to live their lives. However, they are often hindered in terms of executing these decisions due to the underlying physical conditions that make them move to the nursing home.

Staff are often aware of the importance of residents’ autonomy. Moreover, they are motivated to enhance the autonomy of the residents. Nevertheless, staff experience challenges in enhancing residents’ autonomy, such as organizational constraints on choices, time, and available staff (Hedman et al., 2019). Furthermore, processes that hinder the autonomy of residents are often not recognized by staff. Unspoken rules can contribute to the risk of reduced autonomy and participation—for example, regarding what time to get up in the morning and when to enjoy breakfast (Hedman et al., 2019). Furthermore, policies to enhance autonomy are often shaped top-down in the organization without the involvement of residents (Baur & Abma, 2012).

There is considerable knowledge about the autonomy of residents. Moreover, staff members are aware of the importance of enhancing residents’ autonomy and considering their values. However, it remains challenging to enhance the autonomy of residents and bring about change at the unit level.

Participatory action research (PAR) aims to explore and change practices. Questions arising from practice, such as how to enhance autonomy, are complex and often described as wicked problems (Rittel & Webber, 1973). There are no straightforward answers to these kinds of questions. The answers will have to be sought with the persons involved: those who live their lives in this environment and those who work there.

The objective of the current study to enhance autonomy is closely related to the key features of PAR (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005). Autonomy occurs in a relational context, where residents live together and collaborate with staff to shape day-to-day life in the unit. Enhancing autonomy requires participation and collaboration. PAR focuses on supporting transformation through empowerment in which participants not only have a better understanding of their situation but also exert more direct control over the change themselves. By doing so, PAR is expected to lead to a process of change in the lifeworld of residents and staff, and thus on a unit level, which might lead to enhanced autonomy (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005).

The aim of this study was to enhance autonomy in day-to-day practice using a PAR approach. This led to the research question: what processes between residents and staff in the PAR enabled the enhancement of autonomy on the unit level?

Methods

Study Design

The researchers chose a qualitative PAR design. This is a cyclical, participatory process of gaining evidence that is used to bring change to the practice environment (Glasson et al., 2008). In PAR, research is not conducted on persons but with persons (Smith et al., 2010); the residents and staff are therefore both participants and co-researchers in the study.

The key features of action research are that it is a social, participatory, practical, collaborative, emancipatory, critical, and reflexive process, and it aims to transform both theory and practice (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005). These key features correspond with the aim of collaboratively enhancing autonomy in the lifeworld of the participants—i.e., residents and staff.

Kemmis and McTaggart (2005) distinguished four phases in the PAR. 1) The reconnaissance phase is seen as the start of the study. In this first phase, the design of the study is aligned with the various perspectives of those involved in the context, relationships are built, the researcher’s own perspective is explored, and the action group is formed. After this phase, the other three phases follow in so-called action spirals, as follows: 2) a planning phase, 3) an action and observation phase, and 4) a reflection phase.

In the second phase—the planning phase—the action group reflects on themes that are identified in the reconnaissance phase, and possible actions are prioritized. In the third phase—the action and observation phase—the chosen actions are explored in daily practice to observe how they contribute to an intended outcome. Observation is also used to generate new knowledge about how these actions contribute to the desired situation. Finally, in the fourth phase—the reflection phase—the participants reflect on the evolution of their practice, their understanding of the practice, and the situation in which they practice. This research design is open and flexible because of its iterative character, in which the output of each step is the input for the following one (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005). The first phase is described in this methods section, and phases two, three, and four are described in the results section.

Ethical Considerations

In PAR, participation is the underpinning principle. However, participants could not be contacted before the approval of the traditional Ethics Review Board, which was not familiar with PAR. To align the content of the ethics application most closely with the practice and aims of the intended research unit, the researchers sought alignment with the unit manager and the contact person of the unit. The application was submitted to the Ethics Review Board of Tilburg University and approved on 26 April 2018 (no. EC-2018.10).

The first author facilitated PAR. To prepare herself, she attended two courses on the theory and application of PAR from the Centre for Person-centered Research Practice and a practice development course (Dewing, 2009). The first author explored (implicit) assumptions about autonomy in advance with a mentor with a background in andragogy who was not involved in the study.

Description of the Context

A nursing home where older adults with physical impairments live was chosen because the organization considered it important to enhance their clients’ autonomy. The nursing home where the PAR took place is part of an organization in the south of the Netherlands serving a small (23,000 inhabitants) and a medium-sized (36,000 inhabitants) town and the surrounding area. In the unit, 23 full-time equivalent staff members were employed. During the PAR, 28 older adults with physical impairments due to chronic illness or older age lived in the unit.

The unit in which the residents lived was built in 2004 and offered each resident a two-room apartment with a private bathroom. All residents needed 24-hour care. Residents had a voice in care moments, in what and where to eat, and in where to spend their time. Residents were offered a choice regarding when, where, and how (morning) care was given. However, showers were offered only a few times a week. Residents could enjoy their meals three times per day, for which nutritional assistants were responsible. The times for a bread-based meal (breakfast and dinner) or a hot meal (lunch) were fixed. Residents could meet and enjoy their meals in one of two living rooms in the unit or the restaurant of the nursing home. Moreover, residents could choose to eat in bed or the sitting room of their apartment. There was choice when ordering warm meals in advance, accommodating religion, taste, and diet. Ad hoc choices could be made for bread-based meals. Assistance was given to older adults who could not eat independently due to physical conditions. Persons with swallowing problems were limited in their choices of what and where to eat due to protocols. The nursing home had spaces for activities and therapy, a restaurant, and surrounding gardens, which could be enjoyed in the residents’ spare time. The nursing home organized recreational activities in which residents could meet others. They could choose activities that reflected their previous and current hobbies and preferences. These included sports activities, a cooking club, and a classical music club. These activities were often facilitated by volunteers and coordinated by an occupational therapist.

The board managers of the organization developed a policy directed toward autonomy for residents. The managers shared the vision of enhancing autonomy via workshops, theatre, theme meetings, dialogue sessions, and an autonomy game aimed at equipping staff to enhance autonomy. The selected unit on which the research took place had initiated earlier pilots to enhance the autonomy of the residents.

Sampling and Recruitment

Autonomy in a nursing home always takes shape in the relationship between the resident who needs care and the staff who provide care (Agich, 1990; Fine & Glendinning, 2005). Furthermore, Hedman et al. (2019) advised considering both the residents’ and staff’s perspectives to enhance autonomy and participation in the nursing home.

The researchers therefore aimed to include five residents with physical impairments and five staff members in the action group. The researchers preferred to include staff members from different disciplines in the action group. In nursing homes, autonomy is manifested in diverse activities in the unit, such as morning care, eating and drinking, and social activities (van Loon et al., 2023). Purposive sampling was used to ensure that persons giving these distinct types of care would be represented: nutritional assistants, nurses, and occupational therapists of the unit were invited to participate. The researchers used convenience sampling to recruit the residents; the motivation to participate and the ability to attend (in terms of health condition and mobility) were decisive.

Recruitment was done by the unit’s contact person, the occupational therapist working on the unit, who was also involved in the two earlier studies conducted by this research group (Van Loon et al., 2022; van Loon et al., 2023). The contact person used the information and informed consent letters provided by the first author.

Results

Descriptions of the Participants and Meetings of the Action Group

Five residents, a spouse of one of the residents, the contact person (an occupational therapist), and four other staff members consented to join the action group. The contact person reported being sick for a long period, and one of the residents withdrew her involvement after eight months due to a deteriorating health condition. The first author, as facilitator planned an individual dialogue with both persons to reflect on, and close their participation in the process. Another occupational therapist replaced the contact person. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants in the action group.

Meetings of the Action Group

The researchers were aware, based on the literature, that power issues between residents and staff could occur in action research (Baur & Abma, 2012; Jacobs, 2010). Attention was given to the vulnerable position that residents can have as participants within an action group. In the action group, both groups had to assume the role of equal and collaborative partners, causing power shifts. This can lead to withholding important information and providing desirable answers instead.

Because the researchers wanted to include the voices of both groups in the study, they decided to work with a heterogeneous action group, which was alternated by a homogeneous group meeting of residents. Baur and Abma (2012, p. 1055) recommended that residents have mutual space between themselves for ‘enclave deliberation’. The residents could articulate and exchange thoughts and options among themselves and put them forward jointly in a heterogeneous group. To create a safe environment, the subgroup of residents was scheduled every two weeks. The joint action group of residents and staff met every four weeks.

The meetings were organized on the ward itself, considering activities planned by the residents themselves or from within the nursing home and staff shifts, so that the possibility of participating was maximized. Given the health conditions of the participating residents, each meeting was planned to last a maximum of one hour.

During all gatherings, the facilitator opened and sustained a communicative space. Communicative spaces are described by Kemmis and McTaggart (2005) as situations in which persons together attempt to achieve a mutual understanding of a situation and find ways of acting collaboratively. Space can be seen as physical—the place on the unit—or as conceptual, creating circumstances for the action group meeting (Bevan, 2013). During facilitation, the first author followed the group’s process and refrained from intervening with what, who, and why questions.

Traditionally, dialogues take shape using words. However, words can have different meanings for participants. Giving words to feelings and experiences is a cognitive process. Creative work forms can help convey matters that are difficult to put into words. To share this implicit knowledge in a dialogue, the insights subsequently need to be transformed back into language (Titchen & Horsfall, 2011). The chosen work forms matched the preferences and capabilities of the residents involved. An elicitation method with photocards and cartoons was used to generate a dialogue to create ideas and knowledge about autonomy and participation (Harper, 2002). In addition, more lingual methods were applied, such as word clouds, to clarify and identify shared meanings about ways to enhance autonomy for residents. Moreover, the joint organization and prioritization of text cards with actions was used as a combination of language and creativity.

The facilitator always prepared the meetings, made notes, and combined them with photographs of the process in a report. These reports were not a literal representation of the individual contributions of the participants but instead provided the main points about the proposed actions and their consideration. Depending on the preference of the participants, these reports were sent by e-mail to the action group or printed and handed over by the contact person. At each subsequent meeting, the reports and the proceedings of the intended actions were reflected upon. This joint reflection was also a member check to increase the credibility of the study.

The Planning Phase

Kemmis and McTaggart (2005) distinguished the planning phase as the second phase in PAR. In this phase, an initial exploration of possible actions takes place. A selection can be made, and the action group can choose which actions have the highest priority. In September 2018, the first action group of residents gathered. The facilitator intended to explore the concept of autonomy to have a shared understanding and start. She planned to use creative materials to consider questions such as: “where are we now on the way to exert autonomy” and “where do we want to go”. The last question would be: “what do we need to achieve this goal?”. However, the creative method did not match the desires of those present. The trays of the wheelchairs hindered the residents from reaching and handling creative materials, such as markers, colored pencils, colored paper, and textiles. Furthermore, the residents stated their preference to express themselves verbally. We then used photo elicitation and cartoons as a more verbal creative method. Answering the question of what autonomy is for them, they described what it is not.

Autonomy is not “figure it out yourself”, nor is it “it is your responsibility [whether the aid is used safely]”.

When asked what actions were needed to experience more autonomy in the unit, nine possible actions were immediately mentioned.

- Staff should really know the persons they care for

- Awareness of the organizational vision of autonomy among staff

- Knowledge of the care plan by staff

- Personal access to the care plan by residents

- Awareness of the medical conditions of the residents among staff

- Knowledge of how to use care aids among staff

- Availability of staff during breaks

- A correctly functioning call system and staff responding to calls

- Independent use of the elevator for going out

The residents were still feeling the impact of a long summer with a shortage of (permanent) staff. Therefore, they identified three actions: seven, eight, and nine as being the most feasible to explore at that moment. Proposed actions about the availability of the staff and the call system were bundled together and presented to the staff members of the action group, who were joining the next meeting.

In the first joint meeting, the staff were also asked how they would describe autonomy. In this meeting also photos and cartoons were used. They answered that autonomy is:

“That’s what the residents really want. You have to talk about it on admission and continue to do so during their stay. Having a continuous conversation about autonomy, it can differ every day. Autonomy is about expressing wishes, then staff knows how to help the residents to live their own life”.

They talked about the proposed actions and decided to work collaboratively on the actions about the availability of staff during breaks, a correctly functioning call system, and staff responding to calls. S1 took care of the action concerning the elevator button.

The Action and Observation Phase

In the action and observation phase, the chosen actions are explored in daily practice to observe how they contribute to the desirable situation—i.e., a situation in which older people experience more autonomy over their lives in the unit. Moreover, data about the process are gathered. Together with the colleagues in the unit, prioritized actions were explored. The action group members observed whether and how the actions contributed to the shared objective—in this case, enhancing autonomy. Six action spirals were taken up by the action group.

Spiral 1 October 2018

This first spiral is related to the availability of staff during breaks, a call system that functions well, and staff who responds to calls as an action to enhance autonomy. This action followed from resident’s experiences that staff does not respond or do not respond in a timely manner to the calls of residents when they need help. Residents experienced this, as their autonomy was limited, e.g., not being able to go to the toilet when you need to. The technical malfunctions of the call system made residents feel unsafe, “will it work when I am in need”. According to the residents, the call system should be checked. Moreover, residents asked staff to be timelier when responding to calls (by not pausing at the same time). Participant S5 addressed the call system and asked the supplier to review the complaints. Participant S3 discussed pausing with the team.

The observation of this action showed that the joint action group experienced a faster response to calls. A response could be to let the resident who called know that she/he had been heard and that someone was coming. The technical problems also seemed to be solved. The question of residents to staff to pause in two shifts was not taken up by the staff. The team showed resistance to actions that they had not thought of themselves and wanted to continue to have their break together.

Spiral 2 November 2018

This spiral concerned being (better) able to receive feedback by staff as an action to enhance autonomy. This action came from friction that had arisen in the first cycle about the breaks. How can feedback from the resident be perceived as something positive? Staff sometimes perceived residents as not always nuanced in their feedback. Staff members of the action group said that they did not blame them for that; it could be caused by their health condition. Participant S5 took action; she discussed it with the team and encouraged the staff to ask for feedback at care moments. Staff should address each other when feedback is given behind someone’s back. A poster with feedback rules was displayed in the nurses’ post.

The observation of this action revealed that the residents were now always asked, after moments of care, if it had been according to their wishes. One resident said that she was sometimes ahead of that, being the first to give her feedback. That was often a compliment. “You can learn from things that didn’t go so well”. It felt good and reciprocal.

Spiral 3 December 2018/January 2019

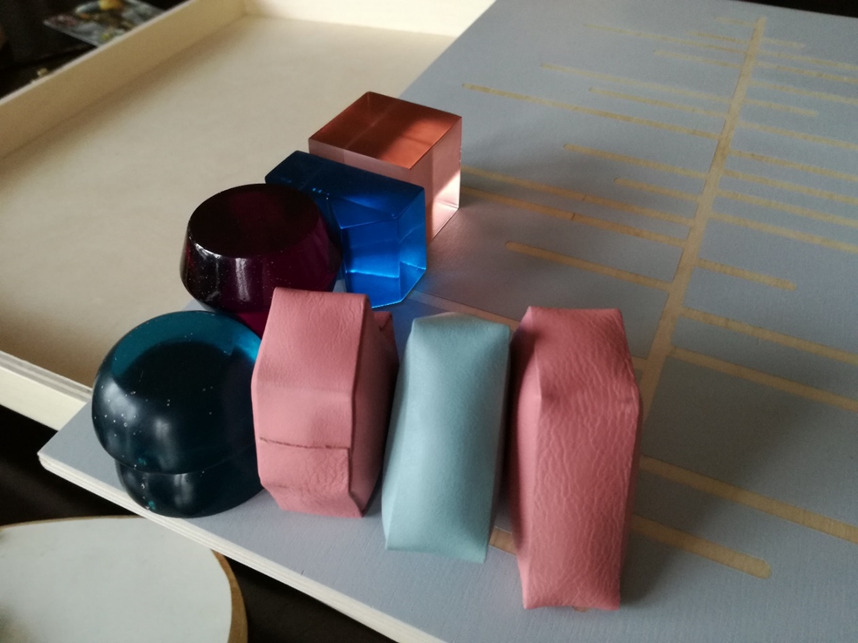

This spiral involved an elevator button that can be used independently by residents as an action to enhance autonomy. This action resulted from the fact that residents with mobility aids could not reach the elevator button and had to wait for someone to press it for them. Participant S1 talked with the housemaster and explored options. After reflecting on spirals 1 and 2, she involved the action group in this process. They collaboratively looked at possible systems in another nursing home (Figure 1) and visited a supplier. Afterward, the residents expressed their preferences.

The observation pointed out that plans like this, should be budgeted for at the location level by the team managers and facility manager. Furthermore, this plan should have included all elevator systems on all floors. The actions of residents and a staff member were not appropriate in the policies of this nursing home and did not lead to a result.

Spiral 4 February 2019

This spiral is related to knowing who is responsible for what in the team as an action to enhance autonomy. This action came from the fact that residents reported or asked whomever of the staff they met. They were then often told that the message “would be passed on”. However, the residents often did not hear a reaction. In the action group, they first heard about fields of attention, such as hygiene or oral care, which were assigned to staff members. They decided to make it known that staff have specific expertise so that residents could immediately contact the person responsible. They posted a list on the ward notice board and put it in the ward information leaflet.

The observation is absent, this action was not reflected on.

Spiral 5 March/April 2019

This spiral concerned direct contact for oral care as an action to enhance autonomy regarding the residents’ agenda. This action stemmed from the discovery that there was a staff member with oral care as a field of attention. There were many complaints about communication from the external dental facility that visited locations with a mobile treatment room. The dentist notified the staff on the ward that they were visiting a particular person. The staff member put a note on the table in the resident’s room. Residents wanted to be able to make their own appointments directly with the dental facility at a time that was convenient for them. “I have more to do than wait for the dentist”, they said. The nurse who had oral care as a field of attention and participant S5 explored the possibilities of changing the way appointments were made with the external dental facility for the residents of this unit.

The observation showed that participant S5 addressed the action with colleagues in the location and with the staff department. No changes were seen. The unit received an evaluation form from the dental facility. Participant S5 reported in the action group meeting that she had completed the form and returned it to the dental facility. She did not involve the action group in this evaluation.

Spiral 6 May/June 2019

This spiral involved a dialogue between the residents and the facility manager about how and where residents prefer to sit when they visit the restaurant. This action stemmed from the fact that some resident members of the action group ate downstairs in the restaurant. There, they sat in a draft in an inconvenient place. They invited the facility manager to the action group. Shortly before they met, the residents of this ward were relocated to the staff restaurant. Staff from now on had to eat in the central part of the restaurant. The conversation with the facility manager eventually focused on the consequences of “being moved” to the staff restaurant; they felt they were forgotten on the serving routes, resulting in cold food.

The observation revealed that the action was taken without the action group. This was the first action that was really prepared in a participatory way; the residents of the action group themselves invited her and collaboratively prepared what they wanted to talk about. They used photo-elicitation for this preparation (Figure 2).

Reflection Phase

The reflection phase connects the findings of the action and observation spirals and attempts to answer the research question. The action group reflected twice, halfway through the research period and at the end. The research group reflected once at the end. The methods of data analysis and data synthesis are explained below.

Data Analysis

The data collected during the PAR process were analyzed using the critical creative hermeneutic analysis (CCHA) method (Van Lieshout & Cardiff, 2011) to answer the research question: what processes occur between residents and staff in participatory action research to enhance residents’ autonomy on the unit level?

This method of analysis was initially developed by Boomer and McCormack (2010) and refined by Van Lieshout and Cardiff (2011) into the CCHA. The latter authors added a participatory, inclusive, and collaborative way of data analysis with research participants to Boomer and McCormack’s (2010) method. The CCHA is based on three principles: the principles of hermeneutics, being critical, and creativity. The principle of hermeneutics refers to finding meaning for a phenomenon. Being critical refers to the principle that a critical discussion should be used to check the interpretation. This interpretation and discussion are executed with the use of creative methods, which provide space for cognitive and pre-cognitive knowledge (Van Lieshout & Cardiff, 2011).

The CCHA consisted of seven steps: (1) preparation: the collected data originating from the action–observation stage were shared with the group; (2) familiarization: the group members read/viewed the data and the members were aware of personal reactions; (3) contemplation: a silent individual consideration of what was read/seen in the data; (4) expression: each group member was asked to express the essence of the data during individual creative expression; (5) contestation and critique: the group members discussed the creative expressions and sought a shared understanding; (6) blending: the group members aimed to find the more manifest themes as well as the more covert ones; and (7) confirmation: a synthesis of the data. In this step, the original data are explored, confirmation of the themes is sought, and the themes are reported (Van Lieshout & Cardiff, 2011).

The action group used the steps of the CCHA twice: on 8 January and 18 June 2019. The CCHA was conducted on the reports and individual experiences of the action group during the process. The dataset is shown in the highlighted column in Figure 11. Example two describes the first CCHA of the action group and illustrates working with the “build your story blocks” (Van Hees et al., 2019).

Collaborative analyses (CCHA) in the research group

The research group analyzed the overall dataset (Figure 11) on 3 July 2019 using the six steps of the CCHA analysis. This dataset consisted of the action group’s reports: plans, evaluations, and reflections; the first author’s reflection log; artifacts, such as collages and photos; and the explored actions. This meeting was recorded and subsequently transcribed.

Data Synthesis

Step 7, data synthesis, was conducted by the first author for both the action group and the research group. To confirm the themes formulated by the action group, she explored the reports of the action group meetings. By rereading the data, the themes found in step 6 of the CCHA were supported. The dataset was limited in size and could therefore be analyzed on paper without the use of an analytical tool such as ATLAS.ti.

For the synthesis of the research group’s data, the first author used ATLAS.ti to explore the original data to confirm the themes. This tool was used because of the comprehensiveness of the overall dataset. Because she sought confirmation of the themes that were found in step 6, the first author deductively coded fragments in the dataset. She considered whether the fragments confirmed and covered the themes or whether important issues were left out of sight. The first author discussed the themes and supporting fragments in several meetings with the second author. Adjustments were needed to the themes and the wording of the themes. Some were merged, and others were split up into subthemes. If a theme was not grounded in the data, it was removed. Finally, the first author reported the rephrased and clustered themes in depth and in detail (Van Lieshout & Cardiff, 2011). The research group discussed the verbatim transcript of the CCHA session and the reported themes and subthemes in a member check. This led to the two themes being merged.

Themes Found in the Analysis

The aim of the study was to gain insight into the processes that occurred between residents and staff in the PAR to enhance the autonomy of residents. The action group found three themes in total in the two CCHA analyses. When the themes of the action group in Table 2 were compared with those of the research group, which relied on the overall dataset, there was a considerable amount of overlap. In the analysis, the action group had an insider perspective and was in the middle of the PAR process. The research group, as outsiders, had another perspective to give meaning to the processes that occurred (Kerstetter, 2012). The themes of the action group and the research group are presented next to each other, such as 1a and 1b, concluding with the themes found solely by the research group.

Theme 1a: Frictions in the Collaboration

The collaboration between residents and staff and between action group staff members and other staff members in the unit regarding enhancing autonomy was predominant in the analysis. According to the staff members in the action group, their colleagues outside the action group mentioned that it seemed as if the residents came up with the actions, and the staff had to carry them out. These colleagues showed anger and resistance and asked whether they did not have a say in this as a team. The proposed actions were perceived as undesirable interference in their way of working, and the proposed action—not to take breaks at the same time to be more available—was not accepted.

Sharing the feelings of the staff members in the action group of being stuck between the action group and their colleagues relieved the tensions between residents and staff within the action group. The residents now understood why the proposed action was not explored. The staff could share their feelings of disappointment that the planned actions did not work out. This process resulted in a new mutual understanding between residents and staff in which they both felt vulnerable to the PAR process. One of the participants (SP) said: “autonomy is like a diamond. It is brilliant material, but so sharp.” With this statement, she gave voice to the situation that autonomy is worth striving for but that you can also hurt yourself and others in the process to achieve it. In this case, because both residents and staff tried to change things, they encountered resistance and friction.

Additionally, it was observed that, at the beginning of the PAR process, actions from the residents’ group were automatically taken over by the staff in the action group. Ownership of the actions was not discussed. Consequently, the actions seemed to be the responsibility of the staff. For future actions, it was agreed that actions would be jointly explored. This happened in May 2019, during action cycle six, when residents and the facility manager discussed the places where residents prefer to sit in the restaurant. Action group members consulted other residents before meeting the manager of the restaurant to discuss their experiences and express their preferences.

Theme 1b: Collaboration between Residents and Staff

The action group members came from a situation in which the residents and staff had their own habits and ways of working in the unit. In the beginning, they described themselves as a community. After some time, when friction arose between the participating residents and staff, it became clear how difficult collaboration was. One of the participants (P6) said:

“We are in need of a tipping point. If I propose something, it is not taken seriously, brushed aside. In the end, it is not going to happen.”

In a conversation between residents and staff of the action group, the perspectives of those living and working on the unit came to the fore, and more understanding was reached as to how this influenced the collaboration in the action group. Power issues were found between the residents and staff in the action group. The staff members felt that they were ordered to take action. Residents felt that the proposed actions were not taken up seriously in the unit. In addition, power issues were present between the staff participants and their colleagues outside the action group. The colleagues felt that the proposed actions were unwelcome interventions in their working routines.

Everyone was impressed that we all want to work towards the same thing and that that can lead to so many emotions. There was a lot of talk afterwards. Several people talked to the manager (S5) and there is now confidence again (Excerpt from an action group report).

After this stage, the participants were more united as a group and were better able to cooperate and feel a joint responsibility to work on actions toward autonomy. This determination was seen in the collaborative actions taken toward the way the residents were placed and served in the restaurant.

The action group has ideas on how to improve the situation. The residents liked the idea of a concrete topic and prioritized this activity. The residents considered this action feasible to bring about a successful conclusion together (Excerpt from an action group report).

Theme 2a: Listening to Each Other

In the second CCHA analysis of the action group, the residents were increasingly involved in the action group, increasingly felt part of the group, and felt seen and heard in the action group, and residents and staff had much more dialogue.

During the CCHA analysis, SP explained her experience with the “build your story blocks” (Van Hees et al., 2019):

“The figures are facing each other. They are talking to each other, they are connected. It is the only way. Not filling in for someone else.”

However, the most important insight was that listening to each other and knowing each other is important and of value, and it helps to bring about change together.

Theme 2b: Learning to Learn Together

Although the first author informed the participants in a letter before seeking consent, there was no advanced knowledge in the action group as to what the change process in the PAR would and should be like. A process of learning to participate together in the action group was revealed. In the beginning, residents in the action group wished to keep their actions to themselves and did not want to share them with other residents and staff in the unit. They only intended to do so when there was some kind of success regarding autonomy enhancement. There was no awareness that other residents in the unit could contribute to actions as well; their possible participation remained overlooked. At the same time, ownership of the proposed actions was not discussed and seemed to be passed on to the staff members in the action group. Later, during the sixth action spiral, this changed, and residents and staff started to collaborate.

There appeared to be a knowledge gap between staff and residents on the unit in general. Staff shared information within the team in reports of team meetings and through an intranet platform; staff used protocols, schedules, and working arrangements, and had implicit customs on the unit that were not known or available to residents. One of the staff members from the action group described her specific role related to hygiene in the unit:

“If there are any new insights [about hygiene], I can then post them on a ‘teams’ website just for the team” (S3).

In the PAR meetings, the residents realized that this knowledge gap existed. As a reaction, the residents did not want to share the reports of their separate meetings with the joint action group or others in the unit. Staff members on the unit mentioned to the manager (S5) that:

“The group is somewhat secretive. What is being said and discussed there? On whose behalf the participants are speaking.”

Eventually, the residents decided to share the actions and experiences of the action group. They discussed how to actualize this:

“Sharing the experience [with the unit] has not yet started. We did talk about a whiteboard before, but how do we make that interactive?” (Excerpt from an action group report).

Theme 3a: Taking Small Steps

The action group experienced that some of the actions they prioritized were addressed, and small steps were taken. For example, the staff reacted faster to the call system, which was one of the proposed actions. An important understanding was the awareness that only small steps could be taken at any time. Change takes time, according to the participants.

The action group members reflected that the residents in the unit expressed resistance when decisions such as where to eat in the restaurant were decided without consultation with the residents. The possible actions proposed in the planning phase by the residents of the action group were reviewed, and some were found to originate from the resistance as described above and were no longer relevant.

Theme 3b: Working Together on Actions to Enhance Autonomy

As mentioned before, the participants in the action group, residents, and staff increasingly worked together as the action group meetings progressed. The exploration of taking actions together led to increasingly inclusive actions. For example, the occupational therapist (S1), a resident (P6), and a manager (S5) visited another nursing home to see how an elevator button was placed in such a way that residents with a physical impairment could use it independently.

Now residents outside the action group were also consulted for preparation of the meeting with the facility manager:

“The residents planned to ask other residents about suggested actions. Are these things that are also of interest to others? Do they possibly have additional ideas?” (Excerpt from an action group report).

Theme 4: Acting in an Existing Role

At the beginning of the PAR process, the staff tended to assume the actions suggested in the action group independently without seeking collaboration with residents inside or outside the action group. This appeared to originate from both the ‘doing for’ culture in their role as staff on the unit, and from a lack of awareness of this behavior in the action group. In the first meeting of the action group, the occupational therapist (S1) said, “I will pick up the action toward the elevator button.”

Later, the staff members of the action group realized that their role in the action group differed from their role as a professional in the unit. They expressed the need for intercollegial conversations about what participating in an action group means for them as staff members. They did not feel free to do so within the joint action group.

The hierarchical role of the manager (S5) turned out to be important for the actions proposed in the action group. This was the case, for example, in the action of an adjusted elevator button to enable residents in wheelchairs to move independently to other floors of the building. All the managers of the location should have budgeted this adjustment. Neither the residents nor the staff in the action group were able to realize this action. Even S5 could not actualize this on her own; however, she could put the elevator button on the agenda with her colleagues.

Theme 5: Needing a Shared View of Autonomy

To achieve a shared understanding, the action group explored the meaning of autonomy at the start of the change process. At the start of the PAR, the participants indicated that they obviously knew what autonomy was. The organization formulated and shared a clear vision of autonomy, and action group members joined to enhance the concept. When asked to explain what it meant, the residents said:

“Autonomy is not ‘figure it out yourself’, nor is it ‘it is your responsibility’” (P1).

The staff described it as follows:

“Autonomy is about what the residents really want. You must talk about it on admission and continue to do so during their stay. Having a continuous conversation about autonomy because it can differ every day. Autonomy is about expressing wishes. Staff needs to know how they can help the residents to live their own life” (Excerpt from an action group report).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to enhance autonomy in day-to-day practice using a PAR approach. The following research question was answered: What processes between residents and staff in the participatory action research enabled the enhancement of autonomy on the unit level?

Eight themes to characterize the processes were distinguished. The action group identified three themes: 1) frictions in the collaboration; 2) listening to each other; and 3) taking small steps. The research group found five themes: 1) collaboration between residents and staff; 2) learning to learn together; 3) working together on actions to enhance autonomy; 4) acting in an existing role; and 5) needing a shared view of autonomy.

The action group found three themes in total in the two CCHA analyses. This might have been because they were themselves in the middle of the process when they reflected on it. The issues that were most prominent at that moment could have come to the forefront. When the action group’s themes were compared with those of the research group, which relied on the overall dataset, there was an evident overlap. The themes of friction in the collaboration and collaboration between residents and staff were similar. The overlap also applied to the themes of listening to each other and learning to learn together and themes of taking small steps and working together on actions to enhance autonomy.

The process in PAR showed an unfolding of participation in the collaboration between residents and staff during the year the research was conducted. The participants moved from learning to collaborating as an action group toward learning to learn together, to eventually being able to decide jointly on inclusive actions and act together. Below, some of the barriers that occurred in the collaborative process are discussed. Subsequently, the authors discuss the participation of residents and staff in the research and the actions undertaken.

How the Processes in the PAR Affected the Residents

In the planning phase, the residents in the action group mentioned many ideas to enhance autonomy in the unit. However, they did not take up the actions themselves and implicitly left this to the staff in the action group. It is possible that the participating residents were acting in their roles as residents. For residents, it is not common to engage in the organization of the unit, such as schedules, break times, and available devices. Baur and Abma (2012) also found this stagnation in the study of older adults participating in a change process in a nursing home: the residents got stuck in their complaints and did not believe that the organization was going to act.

It was felt that residents acted in the way of ordering the staff to start actions, a power issue which was not anticipated by the first author because the literature about power issues in heterogeneous groups indicated the opposite effect (Baur & Abma, 2012). Because she expected power issues between staff and residents and planned a separate meeting of the residents without staff every two weeks, she assumed the staff would be dominant in the dialogues. It seemed to be the other way around. In other studies, this process of protecting participants is described as having a negative impact on the process of collaboration (Jacobs, 2010). In hindsight, the protection of the residents in the PAR process was an inconvenient choice.

Furthermore, the residents in the action group wanted to keep information to themselves until an action was successfully completed. This hampered the other residents in the unit from becoming part of the process of enhancing autonomy. In addition to the advantages of enclave deliberation in a homogenous group, as highlighted by Baur and Abma (2012), enclave deliberation is also seen to create challenges in participation. This may allow a development in the group process that considers the unity of opinions within the group itself to be of greater importance than connecting with others outside the group and the study itself (Karpowitz et al., 2009).

How the Processes in the PAR Affected the Staff

The staff reacted with independently assumed actions without the participation of the residents in the action group. It seems that staff tended to respond in their primary role outside the action group—for example, as nurses or occupational therapists. The pitfall of underestimating the abilities of older adults to engage in PAR was also found by Blok et al. (2022). The staff members were probably not aware that the role of the residents could be altered when participating in an action group. The problems in the collaboration revealed that the good intentions of the staff in taking up actions to enhance autonomy did not always lead to the desired outcomes. Becoming aware of one’s own behaviors during the process could be perceived as stress-inducing. Hedman et al. (2019, p. 287) mentioned “unspoken rules” in the nursing home in this context. Kemmis (2006, p. 461) referred to this process as “unwelcome truths” that can emerge during action research. However, he argued that to achieve real change in practice, researchers should actually look for those unwelcome truths.

How the Learning Process Was Affected

The learning process in the PAR to collaborate in joint actions could have been expected because none of the residents and staff had participated in research such as a PAR before. Although the PAR process was addressed in the information letter to recruit the participants, they did not know what would happen along the way or how and what to expect from their participation. In hindsight, the researchers should have considered the skills to participate in the study. Corrado et al. (2019) stated that older adults should have an equal level of competence to participate in PAR.

Topics such as ownership of actions as a joint responsibility were not discussed in the group but left open. The difficulty and importance of creating joint ownership over the study and the processes was also found by Reed (2005) and Muller-Schoof et al. (2023). Muller-Schoof et al. (2023) mentioned that this can occur when there is no clear discussion at the very start of the study about what the principles of participation are and what they imply. According to Bendien et al. (2023), an open conversation about how the process of collaboration was going in PAR could possibly have prevented this.

Although initially there were problems with learning to work collaboratively, the participatory approach to supporting autonomy at the level of daily life in the unit seems promising. A method such as practice development can also be used with the sole intention of collaboratively enhancing autonomy in the unit (Dewing, 2009).

Actions Aimed at Enhancing Autonomy

During the PAR, six actions were taken up by the action group. The participants were invited to propose them. Particularly the residents used that opportunity. The actions seemed to go in all directions and did not seem to have much coherence. However, the proposed actions that originated from the lifeworld of residents were surprising and quite different from the policies developed from the organizational perspective to enhance autonomy, as found in a previous study by van Loon et al. (2023). Precisely, because the participants suggested the actions, they could help to enhance acceptance of the proposed actions. This makes it valuable to listen to the ideas of residents and staff at the unit level.

After the actions were undertaken, the residents of the action group reflected on what they saw as a result. However, no effect study was done on the actions themselves. Although participants mentioned in the observations during the action spirals that small steps were taken, the outcomes were not conclusive.

Participation of Residents and Staff in Research

Older Adults as Participants

The residents in the action group were involved and played an active role. In most studies, older adults are left out or are not seen as co-researchers. There are ageist beliefs about the ability of residents to act as participants in PAR (Corrado et al., 2019). In the current research, it was the residents who put issues on the agenda and suggested actions. This shows that the residents were able to be both participants and co-researchers in the PAR. Notwithstanding their physical impairments, they were able to identify, prioritize, monitor, and evaluate actions. The group remained intact for the most part throughout the research period; only one person had to step down due to health reasons.

Staff as Participants

The staff realized that engaging in action research to enhancing autonomy also affected them. They expressed the need to talk about this through peer supervision. The involvement of staff on the level of the unit in research in long-term care is not usual (Bekkema et al., 2021). This probably made the researchers misjudge the vulnerability of this group. At the same time, including them was valuable because it was they who eventually explored the actions, first by themselves and later together with the residents. Bekkema et al. (2021) also found in their PAR research that by involving the experience of the staff in a nursing home, crucial knowledge was generated, and matching solutions were identified.

Strengths and Limitations

To ensure the trustworthiness of the study, the quality criteria of credibility, transferability, dependability, confirmability, and reflexivity were considered (Korstjens & Moser, 2018).

Credibility concerns how true the results of the study are. This was increased through the prolonged engagement of the first author with the nursing home unit. She was present every two weeks during the year; she built trust and invested time in getting to know the residents and staff. The unit manager and contact person of the unit developed the design that was submitted by the Ethics Review Board and the initial planning of the research, together with the first author. As discussed above, the action group stayed largely together during the research period, which showed a strong commitment. Despite residents’ health problems that prompted the move to the nursing home, they were able to engage in collaborative action toward autonomy.

Because of the participatory nature of the research, information was given, laid down in reports, shared with all participants, and analyzed by the participants of the action group itself through the process of action and reflection. The participation of older adults in the data analysis is rather new according to Corrado et al. (2019). This member check also increased the study’s credibility.

A limitation is that the findings of the current action research are generated in the practice of the unit under study, a nursing home where older adults with physical impairments live and where staff work. However, the processes that have been identified are relevant to other settings. To enable the transferability of the processes to other contexts, the researchers provided a description of the context, the participants, and the methods used.

Dependability means that participants assess the findings, interpretations, and implications of the study (Korstjens & Moser, 2018). Given the participants’ presence and analysis in the PAR, the dependability of the study was enhanced. Furthermore, a strength is the presence of a rich dataset that encompasses the reports of the action group, evaluations of the process of the action group, a log with reflections explored with the research group and external mentor, the proposed actions and actions taken, and artifacts, such as photos, posters, and association materials.

A strength is that the joint analysis and interpretation in the CCHA were applied to the overall dataset. After following the six phases of data analysis, the conformation of the themes—phase seven in the CCHA analysis—was sought in the dataset. This was done by the first author, who deductively coded the fragments of the dataset with ATLAS.ti using the themes that were found. She analyzed the output of this exploration and discussed the themes and the assigned codes with the second author. Finally, the first author reported the rephrased and clustered themes. Going back and forth in the data heightened the confirmability.

Another strength is that reflexivity—i.e., systematic consideration of possible bias—was addressed by the first author throughout the study period. Being aware of values allows the researcher to understand and give meaning to the research process (Finlay, 2002). She reflected on her values before (2016–2018) and during the research process (2018–2019) with an external mentor.

The first author also reflected on using a log and explored this log with the research group. One example is that the tensions in the action group hindered the collaboration. She reflected on this with the mentor and the research group and decided to wait until the process worked. She withheld from fixing the process (Scott, 2013). These tensions are an inherent part of the dynamic process involved in participating in the PAR because it changed the ways of interacting with each other. The first author used inclusive language and slowed down the pace, when necessary, without laughing or talking issues away. The group itself needed time and space to start working in a collaborative way.

There is a delicate balance between the theory of conducting action research methodically and how it works in practice (Cook, 1998). A strength of the study is that it enabled observation of how action groups worked in practice, which is not always systematic. The action group did not consistently act or reflect upon all actions. Some actions were taken between action group meetings by individuals and not in collaborative action between (some) residents and staff.

The use of creative methods for dialogue needed further exploration for the residents in question, who were older adults with physical impairments living in a nursing home. The residents’ wheelchair trays hindered the use of creative materials, such as markers, glue, paper, and fabric. The residents also preferred a language-based dialogue. In PAR, creative methods are ideally used to facilitate and enlighten conversations (Titchen & Horsfall, 2011). After some experimentation, a combination of creative and verbal methods worked well. The use of “build your story blocks” (Van Hees et al., 2019), cartoons about autonomy, and photo elicitation (Harper, 2002) did the intended use of creative methods in the dialogues and the data analysis (CCHA) (Van Lieshout & Cardiff, 2011) justice. Example 3 illustrates the use of photo elicitation. The use of the “build your story blocks” is illustrated in example 2.

Implications for Practice and Future PAR Research

Organizations or units that aim to address the autonomy of older adults should consider using a participatory method, including residents and staff as partners. An informal, temporary collaboration on an important issue is also found as a promising way to achieve a common goal by Baur and Abma (2012). They position participation at the unit level against the scarce influence of formal participation, such as in client councils. In this way, both participation and autonomy can be enhanced in the lifeworld of the residents.

Physical capacities should be considered when choosing methods: creative work forms are not always appropriate for the targeted population.

Enhancing autonomy needs a culture change, and it is not achieved quickly. A long-term commitment to enhance autonomy with collaborative action on the level of the unit should be realized. All persons involved should be included. This also concerns residents and staff who did not participate in the action group itself. This is in line with Baur and Abma (2012), who recommended taking up a prolonged facilitated process, including actions and sharing of the results with those not directly involved. Making arrangements to involve staff who are not participating is advised. This might support staff members in the action group. This can create opportunities to share the proposed actions and to increase the support to explore them in the unit. It is also advised to share the experiences of the participatory process and actions outside the action group, in the unit, and in other units in the nursing home. Other units and locations can learn from the process and the results of the actions on autonomy.

There are four lessons to be learned from the facilitation of the process.

First, the staff and residents themselves should participate early in the design of the study. They might have been able to indicate how they envisioned the participatory meetings and reacted to the proposed design. The separate meetings that were used in this study for the residents can be patronizing for one part of the group and disregard the vulnerability of the other part (Jacobs, 2010).

The second lesson learned is that the process of cocreation is not understood by all participants. Muller-Schoof et al. (2023) experienced the same in the PAR they conducted. In preparation for the PAR process, it may be useful to share expectations of how this process of co-researching might go in practice (Bendien et al., 2023). A significant focus in this regard is that it is not just about proposing actions but also about jointly considering actions, exploring, and evaluating them.

The third lesson concerns the consideration of the first author not intervening in the communicative space. The participatory nature of the research requires a facilitating approach to support participation. Involvement and collaboration between all group members is essential. In this particular study, the first author was an outsider who facilitated the process but did not interfere with the decisions about the actions. She had no preferences in what actions would be chosen as long as they contributed to enhancing autonomy.

An unintended consequence of this approach to facilitation was that it created tensions when the residents and staff were confronted with each other’s perspectives and needed to find a way through the process. During PAR, the researcher experienced constant deliberations of “to move ahead with the process or to stand still” and “create space for whatever does happen or to direct the process in the action group” (Van Lieshout et al., 2021, p. 129).

The advantage of this method of facilitation was that it stimulated learning and transformation by the group itself. The researcher could have addressed these processes in the group to a greater and more frequent extent.

The fourth lesson is that action spirals should be continued longer until actions are completed. In this study, many actions were proposed and started but were not fully explored. Having a facilitator involved in preparation and support is essential to ensure progress in the group process.

Conclusion

This study answered the research question: what processes between residents and staff in participatory action research enabled the enhancement of autonomy at the unit level?

The participation of residents and staff and the collaboration between them made the learning process, to collaborate and participate, visible. It was a dynamic and challenging process to be able to learn together, to listen to each other, and to meet on a reciprocal basis, relying on each other, not taking over, and having influence but having the courage and the shared will to enhance autonomy.

The process of working with an action group supported by a facilitator helped identify and explore actions jointly to enhance autonomy. When a change in daily practice is taken up in collaboration with those concerned, the process aligns with the lifeworld of residents and the work of the staff in the unit. This is a promising method for enhancing autonomy in daily practice.