Introduction

Current school systems are not necessarily designed for all students. While some students may thrive at school, others struggle to flourish. Multitudes of factors play into these complexities, many of which have been explored in extensive detail. For example, through research into school connectedness (Pate et al., 2017), whether it matters if students (dis)like school (Graham et al., 2022), or the role that teacher-student relationships have on the student experience (Roorda et al., 2011). While some research into student school experiences incorporates student perspectives, there is less that explicitly includes students as co-designers of a tool that enables them to become co-inquirers of their own and others’ experiences. This project provided the opportunity for students disenfranchised with mainstream schooling to co-design a data collection tool that could be used to find out from other students why school works for some students, but not others. Young people often think about and experience school differently and may have different ideas about what is important to ask and how experiences could be changed. As well as being experts in understanding their own school experiences, engaging with those for whom school was not working provides invaluable insight into what they feel matters about the school experience and potential opportunities to change trajectories. Their reflections and recommendations expand the pool of available knowledge both in terms of factors contributing to student experiences of school, and opportunities to engage students and those who support them in participatory research that makes a difference to them.

Co-design in Research

Co-design as a method has been in use since the 1960s, defined by Zelenko et al. (2021, p. 229) as “a form of participatory design approach [that] attempts to actively involve all stakeholders in the design and development process to ensure the outcomes meet all necessary needs … [which is] based on the premise that people affected by design decisions should take part in the making of those decisions.” At the school level, Mutch (2016) proposes a continuum of engagement of children in research, from child-related research for children, moving through child-focussed research on or about children, to child-centered research with children, ending with child-driven research by children. The project described here fits into the child-centered phase, where “children might be engaged in the design, implementation, or sense-making … [and are treated as] partners in the research” (p. 7), and also into what Zelenko et al. (2021, p. 239) describe as a “reversal of expertise,” where the power to design the tool was put into the hands of the students.

Student Voice

From Dewey (1916) onwards, the importance of listening to students about what matters to them has been established as critical for education (Cook-Sather, 2006; Lundy, 2007). Fielding (2001) suggests that there are three levels of student participation in student voice work: sharing opinions, collaborating with teachers, or taking on leadership roles — this research uses the sharing of student opinions in conjunction with collaboration on the tool’s refinement. Students provide unique insights as “they are able to throw light upon the causes and nature of learning and behaviour difficulties that might be overlooked or not mentioned by teachers” or that “are likely to be in conflict” with staff perspectives (Cefai & Cooper, 2010, p. 184). Student voice is particularly important for disenfranchised students who are already struggling with schooling and can occur by using various techniques including through community forums (Baroutsis et al., 2016), input to evaluations (Bourke & MacDonald, 2018; Giraldo-García et al., 2020; Te Riele et al., 2017), or through valuing Indigenous and other perspectives (Wallace, 2011). As Chappell (2022, p. 216) notes, “When student voice is valued and implemented the opportunities for growth and leadership are unlimited.”

Participatory Analysis

Participatory analysis, first coined in 1993 by Frank Laird, describes an amalgam process originally designed to meet the expectations of both pluralist and direct participation democratic theorists for the development of science and technology policies. Participatory analysis requires active involvement and learning by participants, including being taught to “analyze the problem at hand” as well as “how and when to challenge” the facts, data, and very questions being asked to frame the investigation (Laird, 1993, pp. 353–354). Participatory analysis has recently been used in research on geography (Caretta, 2016), healthcare (Switzer & Flicker, 2021), and migrant children (Ryu, 2022). While there are many descriptions of ways to involve participants in research data analysis (Cahill, 2008; Chatterton et al., 2008; Green, 2020; Richardson, 2002; Rix et al., 2021), in participatory analysis processes, there is “little guidance on how to meaningfully and respectfully work with children and youth in ways that are authentic; where academic voices do not dominate” (Liebenberg et al., 2020, p. 3). Informed by the project lead’s prior research inviting similar participatory analysis processes with primary school-aged children and young people (Gillett-Swan, 2014, 2018), this project used participatory analysis (described further in the following section) as part of both the initial tool evaluation and during the “Talking Tree” tool’s development.

How the Tool was Developed

Tool development took the form of a series of advisory group sessions that occurred across two high school sites over a 12-month period. Each session for each site involved up to ten students. A staff session was also conducted at approximately the mid-point of the student sessions and involved teaching and non-teaching staff, including those involved with student support (e.g. Guidance Officers/School Counsellors, Cultural Support Workers), and members of school leadership.

The following steps were involved in the tool development process:

-

Advisory group sessions in focus group format

-

Data analysis (by students and researchers)

-

Tool development

-

Student feedback on the tool

The first phase of the process included focus groups with students that focused on developing, with the students, a way to explore why school works for some students, and not others.

Guiding discussion questions were printed and placed on the table along with several packs of coloured sticky notes and pens. Students tended to begin by writing thoughts, ideas, or words on sticky notes, which then tended to evolve further into group discussions as they read what one another had written on the sticky notes (see Figure 1), leading this project closer to Mutch’s (2016) co-research end of the continuum.

In thinking about how the topic of “why school works for some and not others” could be explored with other students not involved in the co-design process, students recounted some of the factors influencing their own experiences of school, including what they observed as what worked and what didn’t, and examples of their former peers’ or their own experiences. Students used these examples to illustrate the points they considered most relevant for the discussion and for potential inclusion in the tool.

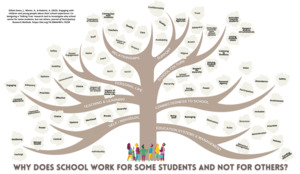

Students also suggested questions that could (or should) be asked when exploring this topic with other students. Sometimes this incorporated their reflective insights on how their current schooling context was working for them (e.g., the questions that staff in their current schooling context asked them, how student-staff relationships were developed differently, or different ways that the school policies, practices, and processes were structured that really worked for them). Other times, these suggestions were based on what they wanted to be asked, or noticed when involved in a school that wasn’t working for them. Students also learned about and evaluated different data collection tools and techniques using different evaluation strategies (see Figure 2 for an example).

Tool exploration and evaluation took the form of providing 20 double-sided laminated cards created by the researchers that had a title and image on one side (see Figure 2) and a brief description/explanation of the tool(s) on the other. The tools were selected based on an extensive review of research methods materials and drawing upon tools and strategies used in prior research conducted by the project lead. The tool examples included common research tools (e.g. surveys, focus groups, interviews, drawing), innovative/creative tools (e.g. games, video narratives, journey mapping), and participatory examples (e.g. provocation cards, advisory groups, student inquiry). The researchers brought enough cards to each session for students to be able to explore the tools individually or in groups of their choosing. Students were also invited to share any other ideas and research tools they were familiar with as part of the discussion. The approach to exploring and evaluating the different tools differed within the groups and across the sessions. For example, some students broke off into pairs or smaller groups to review and discuss the cards before coming back together as part of a bigger group; others sorted the cards into piles of things they wanted to know more about and ones they were not interested in or did not feel that others their age would engage with; and others engaged in a roundtable discussion and deliberation process prior to shortlisting possible approaches they wanted to evaluate.

One group chose to carefully deliberate each tool using a comparative and consensus method, a process that evolved organically as the students negotiated between themselves how they wanted to go about determining possible options. To do this, each person had their own set of cards, which they individually grouped into either three or four piles: Like, Don’t like, Sometimes like, and, if there was a fourth pile, this was generally along the lines of “I don’t like but others might.” The students then matched who had put which card in which pile to determine a shortlist with consensus. That is, the cards that all students had included in their “like” pile, were included in the group “like” consensus pile. Any cards that did not have consensus — that is, all students nominating that they either liked/did not like it as a strategy — were put in a third group pile. These students then went through the third pile to discuss what they liked/didn’t like in an attempt to resolve and negotiate the tension. If the tension was not resolved — that is, no one wanted to switch how they had grouped the card —it remained in the third group pile. This process was entirely led and determined by the students, with the research team observing the process and occasionally being invited into the conversation. For example, members of the research team became involved if the students wanted more information about a particular strategy, or to see whether an example they had thought of would be grouped within the card classification that they thought it may fall under. The Research Tool Evaluation template sheet was available for anyone that wanted to use it; however, some students chose instead to use sticky notes on top of piles, some chose to verbally provide their views either directly to the audio recorder and/or researcher or group deliberation discussion, and some chose to use a combination of these strategies.

While individual students may have had different preferences in terms of their own preferred ways of being involved in data collection as a participant (e.g., individually, in groups, writing, talking, drawing, etc.), across each of the groups and sessions students emphasized the importance of having time and space to talk, and someone who genuinely wanted to listen and cared about what they had to say. From here, the idea of a research stimulus that could be used to support or initiate discussion/conversation with students came about as an early version of a potential co-designed research tool.

Developing the “Talking Tree”

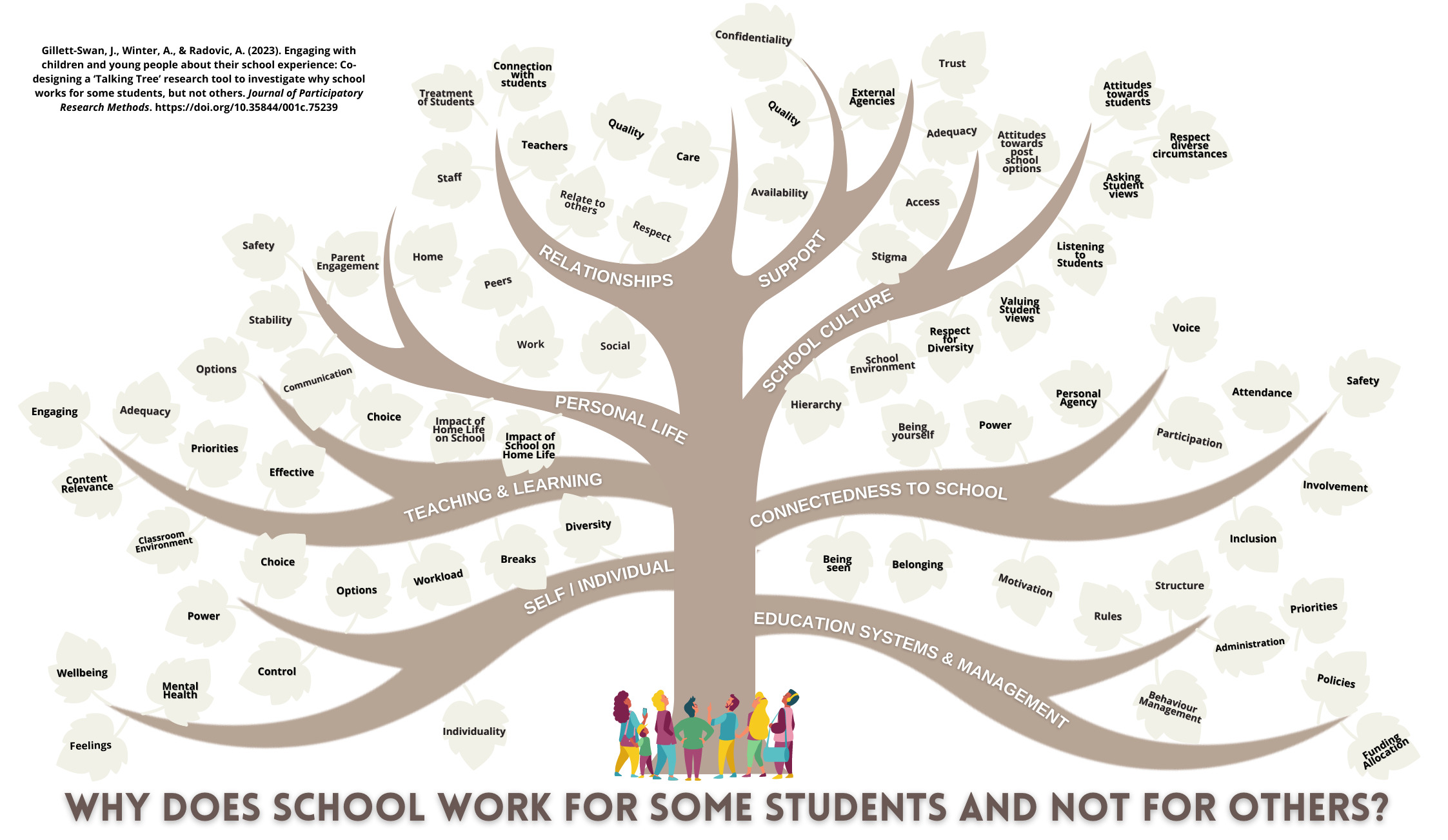

As the research team mapped the interconnections between the different research data elements identified by students, the formation resembled a treelike shape. From that point, the researchers followed the tree idea for further feedback and input from the students in subsequent sessions.

Students’ thoughts (both from the sticky notes and the transcribed focus group discussions) were brought together and transferred onto laminated, leaf-shaped printouts (Figure 3).

These leaves were used in the following sessions with students where they analyzed and grouped the leaves in clusters that made sense to them (see Figure 4). Similar participatory analysis processes with children and young people have been used in previous research conducted by the lead researcher in other projects (e.g. Gillett-Swan, 2014, 2018) and by others (Liebenberg et al., 2020).

This process was completed by students and researchers in separate sessions. A similar process to the student data collection activities was conducted with staff. Staff were also shown the information generated by the students on the leaves as part of their research activities and provided with the opportunity to reflect on what the students had shared and provide additional layers of insight.

The research team collated the information provided by students, staff, and researchers to create multiple versions and representations of the intersections, commonalities, and points of divergence in the analyses. The researchers considered multiple clusters of information as perceived and proposed by the students and staff participating in the research. Researchers considered this information, together with the analyses participants completed, and the clusters of information the researchers separately identified when analyzing the same data. These findings were then refined and distilled into the development of the “Talking Tree” tool (see Figure 5).

Why it was Developed

The “Talking Tree” tool was developed to present research data in a visually logical sequence, intentionally designed to be easy to follow and read. The information is presented in a way that indicates interconnections between diverse student insights about their school experiences.

The “Talking Tree” tool was shared with the students for their feedback, interpretations, and further input. Amendments were made to create the final version. One of the feedback items received was that the Tree can be used to initiate and facilitate meaningful conversations about why school works for some students while it does not for others. In addition, students provided suggestions about how the Tree could be tailored to various research participants’ needs or preferences. The branches were amended where suggested by students, and their ideas for the Tree’s possible use and incorporation in future conversations with students about their school experiences are included below.

How to use the Talking Tree tool

Students had several suggestions for how the tool could be used:

-

Talking point/discussion prompt stimulus. The information shared on the leaves and branches can be used to prompt conversations about different aspects of school, or personal life/life outside of school, to stimulate conversations about why school does not work for some students, and why. All or some of the elements can be explored in more depth, and participants can be asked if any aspects resonate, and why, or if there are any elements that are missing and should be added to the tree. Depending on the time available and the context, these conversations can then be expanded to gain further insights into the students’ school experiences. While each leaf and branch may be interpreted differently by those engaging with the resource, a glossary with examples has been included with this resource document to reflect the meanings attributed by students who co-developed the tool.

-

Color your experience. Students or staff can be invited to color the leaves and/or branches in a way that assists them to distinguish the elements of the tree according to the “categories” they identify as important, e.g., impactful, confusing/unsure/unclear, resonating, significant/insignificant, relevant/irrelevant, contentious, etc.

-

Split tree. Students or staff can use the tree as a stimulus to think about different factors that contribute to their experience of school to create a representation that shows what is working on one side, and what is not working on the other.

-

Create your own representation. The remaining space on the “Talking Tree” tool can be used to add any further ideas or thoughts that students or staff find relevant. They can also be encouraged to create their own interpretation of the information shared on the tree in whichever format they may find suitable. For example, in the session where students provided feedback on the tool, one student used it as a stimulus for drawing a brick wall where each brick included a word and was either rough or smooth-edged. The student described the wall as being able to represent the blocks that build the schooling experience with some that help to keep the foundation strong (smooth edges), while others weaken it (rough edges).

-

Student and Staff Collaborative Inquiry. Schools could use the tree as a starting point to conduct their own research inquiries in their school environment. Students and staff could focus on different aspects represented in the tree or develop new leaves and/or branches to extend and expand upon the key areas of relevance to them and their school communities. These inquiry projects could be progressed independently but concurrently, OR in an aligned, collaborative way.

Student perspectives on how to talk to students about things that matter to them

Students value the opportunity to be able to talk about and share their views and perspectives with someone who actually wants to listen and cares about what they have to say. Students want to be recognized as individuals and problematize a “presumed homogeneity” of perspectives that are considered to represent the experiences of all students, in turn failing to recognize the diverse and complex personal and life circumstances of each individual student (Fielding, 2004, p. 302).

Participating students also reflected that there are generally few opportunities for students to share their views and experiences about school. They said when students do have an opportunity to share things that matter, they may be hesitant or provide a filtered response for the following reasons (in isolation or in combination):

-

Past experiences when adults at school have broken their trust. Examples such as: when staff who said they were there to help them then shared things that students shared with them with others (parents, other teachers/school staff, referrals), including when staff had to follow mandatory reporting requirements. In doing so, students said they felt their confidentiality had been breached and their trust in sharing important matters with adults had been broken

-

Lack of follow-up action or support (see also Lundy, 2007)

-

Not being taken seriously (see also Lundy, 2018)

-

Tokenistic or superficial involvement (see also Lundy, 2018)

-

Being spoken about or on behalf of rather than being asked themselves (see also Fielding, 2004; Mayes et al., 2019).

In addition, if their disenfranchisement with school is considered to reflect their level of school interest and engagement, their views may be a “less desirable” voice to seek, given those seeking it may not like what they hear. This reflects what Finneran et al. (2021, p. 2) describe as the selective attention towards particular voices in the school environment as those “that speak the ‘palatable’ language of the school in contrast to those voices that are seen as ‘incomprehensible or recalcitrant’ or as ‘aggressive, rude, or obnoxious.’” Student views may also be less visible or discounted when they conflict with staff perspectives (Cefai & Cooper, 2010).

The views and perspectives of students for whom school is not working may therefore be completely invisible or excluded due to their perception of a lack of people noticing that school is not working for them, which means no one is asking what is going on for them, or because of student reluctance to share. That is, students can feel isolated when school is not working for them, and invisible because no one seems to notice, care, or is trusted enough to share with. School counsellors also recognise the tension between damaging their relationships with students and reporting processes (Brown & Armstrong, 2022), and the complexities associated with staff knowledge and understanding of reporting requirements and processes across different educational systems and jurisdictions (Ayling et al., 2020). Responsiveness was important for these students. Approaching students with genuine care and interest matters; not just hearing but listening and being responsive. Students also expressed that they appreciated teachers and school staff knowing their names, taking initiative and having intentionality in “checking in” with them.

Finally, students feel ignored and undervalued if they share things that are important to them (e.g., to do with mental health, well-being, and safety) and nothing is done. Staff reflected that it may be that things are happening behind the scenes that students do not know about. Closing the feedback loop to explicitly communicate with students who have shared that something is happening, and truly doing something about it, is critical, even if staff are not able to share exactly what these actions are due to privacy or confidentiality. Staff and students reflected that even if the issues raised may seem arbitrary or low priority for staff, they might be a “big deal” for students. Communication on resulting actions can help to develop positive relationships, encourage students to share, and can support students to feel and know that they (and their views, experiences, and concerns) matter and will be taken seriously. Students identified that these actions would also contribute to creating healthier, safer, and more inclusive school environments and experiences for students who may be questioning how well school is working for them.

Conclusion

The Talking Tree presents a tool co-designed with students that enables conversations and deep exploration of student experiences of school to occur in a structured but non-confrontational way. The student co-designers present creative opportunities and entry points for staff and students to talk about potentially complex school experiences in a way that may be more accessible for students for whom school may not be working. Taking time to know students and understand them as individuals is key to supporting students to navigate their school experience. Students valued the opportunity for their views and expertise to be heard, taken seriously, and included in things that may actually help to make a difference in their own and others’ lives at school.

Glossary with Examples

The following glossary provides some examples of what students and staff spoke about in relation to each of the broader categories. These indicative examples are added with the aim of providing context for users engaging with the resource. Overlaps exist both between the concepts displayed on the leaves and the branches of the “Talking Tree,” most of which are mentioned in the sections below.

SELF branch

-

Individuality — Students spoke about the way that some schools do not recognise students as individuals, e.g., “Schools negatively affect kids’ growth as an individual,” “Schools act like everyone has to be the same,” “Everyone is expected to do the exact same thing, even though we are all different and may have different personal things going on.”

-

Mental Health — Students spoke about the mental health issues affecting students including “depressive episodes,” “responding with anger/anger issues,” “social anxiety,” "mental health playing a big role in what makes school work for students, “effects of bullying on students’ mental health and identity, and mental health statistics.”

-

Wellbeing — Students also spoke about how wellbeing and accessing wellbeing spaces is perceived in school context e.g., “Accessing wellbeing spaces can be shameful as everyone knows you’ve been there, and you’re treated like an outcast.”

-

Control, Power, Choice, Options — Students spoke about how much influence they have over what happens to them and how the choices/options available to them can influence their experiences within and outside of school.

-

Feelings — Students discussed the impact of school on their feelings, as well as the importance and impact of their feelings on their school experience.

PEDAGOGY branch

-

Options, Choice — Students discussed the limited options and resources that can help them learn about their options and how that affects their experience of schooling e.g. “Very limited resources to find a school that works for you,” “For some people, homework helps them; other times, homework is just not helping at all,” “Bad options for electives; elective subject teachers are not good,” “Little to no experience or insight about what pathway different elective subjects will lead,” “Schools put too much pressure on students,” “It’s like, you have to be the best, you have to go to uni(versity), you have to get a career. You can’t get a job without an A grade.” There is an overlap between these concepts and the same concepts placed on the “SELF” branch. There is also a crossover with the “Attitudes towards post-school options” concept from the SCHOOL CULTURE branch.

-

Breaks — Students spoke about short breaktimes, and how these affect their school and learning experiences.

-

Workload — Students discussed the impact of heavy workload on their school and learning experiences e.g. “The workload is just a bit much,” “Too many assignments are given at once.”

-

Priorities — Students discussed how they perceived what schools were prioritising, and how that impacts their school experiences e.g., “Mainstream school focuses on graduation but not on transition,” “The older generations just think of mental health issues as if they are nothing,” “In schools, education is more important than mental health.”

-

Content relevance — Students spoke about how relevant they believe the educational content is for their future, and in general e.g., “Schools decide to teach us things that we might never even use ever in our lives unless we decide to be a professor or a teacher,” “Schools don’t teach us what goes on in the world beyond school and education.”

-

Engaging — Students spoke about how engaging the learning experience is for them e.g., “The work isn’t interesting or helpful enough,” “Sitting and just listening to a teacher talk is boring and aggravating,” “You’re not going to pay attention and you’re not going to learn anything.”

-

Adequacy — Students spoke about instruction adequacy (Do the instructional methods used provide students with all they need to know to be successful with the learning objectives? Is what teachers do in the classroom sufficient to support students with what they need?). e.g., “The teachers just sit there and don’t explain anything,” “Teachers do not know how to teach.”

-

Effective — Students spoke about (in)effectiveness of teaching and learning processes as influencing school experience (Do the instructional methods used help students to learn/understand the content?).

-

Classroom environment — Students spoke about how classroom environment impacts their school experience.

PERSONAL LIFE branch

-

Safety, Stability — Students spoke about how safety and stability, or absence of those at home and in school affects them, e.g., “Going out in public is the safest place we can be when school and home aren’t safe places.”

-

Impact of Home Life on School — Students discussed the impact home life can have on their school experience, e.g. “When home life isn’t great and a school is a place that doesn’t care about your personal issues and you have to go there five days a week, of course you’re going to start disliking school,” “Students whose parents want them to stay in school will keep going even if they’re unmotivated.”

-

Impact of School on Home Life including Communication, Home and Parental Engagement — Students spoke about confidentiality not being respected as counsellors/guidance offers/youth workers tell parents everything students talk to them about, and how that impacts their home life, e.g., “Home is meant to be our safe place. When schools call home, it makes it not our safe space,” “Sometimes calling home can put students in more danger than what it’s worth,” “Calling home can make students’ home life even worse,” “Teachers go straight to parents. It’s honestly the worst thing ever for some people,” “Teachers phone home for things that are not serious,” “The more schools call your parents, the more and more the problems come about.”

-

Social and Work — Students spoke about how their social life and their work (if employed) impacts their school experience and vice versa.

RELATIONSHIPS branch

-

Treatment of students — Students spoke about how they felt they were being treated and how that impacted them, e.g. “I genuinely feel like I was being bullied into the person I am today.”

-

Relate to students & Know students — Students spoke about how important it was how school staff/teachers related to them. They also talked about how important it was to them that the school staff and teachers knew and understood them well, e.g., “Teachers don’t understand that students are different, that they have unique needs and circumstances.”

-

Care — Students spoke about how important it was to them to know that the school staff and teachers genuinely cared for them, e.g., “Noticing when things change for students/that school doesn’t work for them,” “Concerns that school isn’t working for students aren’t expressed with care,” “Schools don’t care about students’ wellbeing at all.”

-

Respect — Students discussed how important it was for them to be treated with respect, e.g., “They assume students don’t know anything because they are younger than them.”

-

Teachers — Students spoke about how the quality of their relationships with teachers had an impact on them. There is an intersection between this and other concepts on the RELATIONSHIPS branch.

-

Staff — Students spoke about how the quality of their relationships with school staff other than teachers, i.e., school principal, school administration, guidance officers, counsellors, youth workers had an impact on them. There is an intersection between this and other concepts on the RELATIONSHIPS branch.

-

Peers — Students spoke about how the quality of their personal relationships with peers in and outside of school had an impact on them. There is an intersection between this and other concepts on the RELATIONSHIPS branch.

SUPPORT branch

-

Availability — Students spoke about the availability of support in school and how this impacted them, e.g. “There is often only one guidance officer per thousand (or more) students, which is not enough,” “It’s rare to find a teacher that will actually talk with you about your personal issues and home life, and care,” “No support for kids with learning disabilities,” “There are not enough guidance counsellors to support students,” “They just toss us off to go somewhere else and doesn’t help us at all.” There is an overlap between this and other concepts on the RELATIONSHIPS branch.

-

Quality — Students spoke about the quality of support in school and how this impacted them, e.g., “Guidance counsellors are overworked,” “RUOK day and anti-bullying posters are not enough,” “The school not picking up on the signs of worsening mental health,” “You’re the one that’s going on the journey and not even the people that are supposed to support you know how to do that,” “Counsellors providing advice that isn’t helpful.”

-

Stigma — Students spoke about the stigma surrounding needing/accessing support and how this impacted them, e.g., “Students making fun of others accessing or needing support.”

-

Adequacy — Students discussed the adequacy of support available/provided in schools, e.g., “None to barely any educational support,” “Homework club was provided after school, however, this wasn’t suitable for kids with part-time jobs,” “Guidance officers are the only mental health support provided to students,” “If you are not comfortable talking to guidance officers, where are you supposed to go?” “Anxiety/panic attack cards do not help,” “Being put on a flexible timetable, but after a few weeks being told you have to go back to school full time,” “Primary students are just given therapy or behaviour groups rather than schools trying to learn what’s causing the issue for the student,” “Counsellors not listening.”

-

Confidentiality & Trust — Students discussed the importance of confidentiality and trust and how important those were to them, e.g., “Guidance officers need to respect confidentiality… and they do not,” “Not being able to talk to anyone that you can trust,” “If you try and confide in someone and they tell everyone,” “Guidance counsellors don’t keep what you say to them in private even when they say they will.”

-

Access — Students discussed accessing support. This concept overlaps with “Availability” and “Stigma” concepts from this branch.

-

External agencies — Referring to agencies, organisations, and services that students may be supported by outside of school, and how these may affect their school experience.

SCHOOL CULTURE branch

-

School Environment — Students spoke about their perceptions of the school environment and how these may affect their school experience, e.g., “You might enjoy the school, but system is the problem,” “There is not a single thing schools have done well,” “Schools are not a nurturing environment,” “Everyone is trying to figure out how to fix students when sometimes it’s the school that needs to change,” “The system of education here is condescending,” “In schools, education is more important than mental health.”

-

Attitudes towards students & Valuing and asking student views — Students spoke about the importance of attitudes towards students, and about valuing and asking about their views, e.g., “Not being taken seriously,” “Teachers are not trying to find out why something happened,” “They don’t accommodate or try to learn what’s causing the issue, or what the problem is.”

-

Listening to students — Students spoke about the importance of being listened to, e.g., “Teachers just don’t listen if you have any complaints,” “It’s hard to find someone you feel comfortable talking to and being able to talk to when you need to,” “Students can’t say anything at all or you will get a detention,” “Not listening to students’ needs.”

-

Attitudes towards post-school options — Students discussed their perceptions of schools’ attitudes towards post-school options and how these impacted their school and post-school experience, e.g., “Mainstream schools just focus on getting you graduated, but they don’t focus on your transition out. You’re on your own after that,” “There is a stigma associated with post-school options that aren’t uni(versity). Schools don’t even talk about it,” “Schools do not tell students about all the educational and work options they have,” “Students feel out of the loop and like their options are limited when not all the post-school options are shared,” “It often feels like schools do not even know about all the options available to students,” “You know if school is working for you when you have to choose subjects for your future.”

-

Hierarchy — Students spoke about the school hierarchy and how it impacts their school experience.

-

Respect for diversity and for diverse circumstances — Students spoke about the importance of respecting students’ diversity, the diversity of their needs/circumstances, and how this affected their school experience.

CONNECTEDNESS TO SCHOOL branch

-

Being seen — Students spoke about the importance of being seen, e.g., “It feels like your opinion or whatever you say is not going to really matter in the long run. Like you’re going to get into trouble for it.”

-

Being yourself — Students spoke about the importance of being able to be themselves, e.g., “When you try to explain what’s best for you, they think that that’s completely wrong.”

-

Personal power and agency — Students discussed the importance of having power to control what happens to them and to act for change.

-

Voice — Students spoke about the importance of having their voice heard and being believed when expressing themselves, e.g., “Going everywhere to get help, but no one believes you,” “You have to defend yourself at every moment,” “Not being believed by teachers when sharing serious issues.”

-

Motivation and Participation — Students discussed motivation and what it felt like to not participate in school, e.g., “You don’t seem to be participating at school, but you are at school,” “Less engagement with people at school,” “Not responding to questions,” “Not participating at school,” “Not doing assessments.”

-

Attendance — Students spoke about school attendance and absenteeism, e.g., “Different types of absence from school,” “Not going to school,” “Attendance dropping,” “School refusal,” "Getting to school later and later.

-

Belonging, Inclusion, and Involvement — Students discussed these as being important aspects of school experience.

-

In this branch there are also crossovers with multiple elements of the PERSONAL LIFE branch, such as the concept of “Safety.”

EDUCATION SYSTEMS & MANAGEMENT branch

-

Behaviour management — Students discussed the effectiveness of behavioural management strategies, e.g., “Pushing an agenda that only one type of behaviour is acceptable,” “School suspensions provide no peer connection during the day, which can be really damaging for your mental health,” “Students treat suspension like a vacation,” “Schools act like it’s the end of the world and like you’re a bad person if you misbehave.”

-

Administration and Rules — Students spoke about their perception of the school administration’s priorities and rules, e.g., “School administration prioritises filling in forms and class attendance to students’ wellbeing.” This concept relates to the “Priorities” concept from this branch.

-

Priorities — Students spoke about their perception of school priorities, e.g., “Mainstream schools pursue excellence and greatness rather than students’ wellbeing,” “Schools care more about attendance than what’s really going on for a student,” “Mainstream schools just focus on getting you graduated, but they don’t focus on your transition out. You’re on your own after that,” “People in the main offices, like deputies and principals have heaps of work, but they are just there for their work, not for the kids.” This concept overlaps with the “Priorities” concept from the PEDAGOGY branch.

-

Structure, Policies, Funding allocation — School staff discussed how school Structure, Policies, and Funding allocations impact school experience for both students and staff.

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to thank and gratefully acknowledge the time, contributions, and expertise of the students and staff involved in co-designing this tool. Their insights and contributions have been invaluable in understanding more about what students for whom school wasn’t working feel is important to know more about, and what the dedicated staff working with these students feel could, or should, be asked when it comes to finding out about student school experiences. Understanding more about why school works for some students and not others comes with the vision to help school communities to modify the school experience so it is more likely to work for everyone.

This project was funded by a QUT Women in Research Grant. This project received Ethical Clearance from the QUT Human Research Ethics Committee, and Research Approval from the Department of Education, Queensland. The views contained in this article are those of the authors and participants, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Education Queensland.