Over the last decade, the wheelchair sector has dedicated substantial efforts to improve the competency of rehabilitation professionals and lay health workers engaged in wheelchair service worldwide (Allen et al., 2019; USAID, 2015). As defined by the World Health Organization, wheelchair service refers to service through which wheelchair users access trained personnel to assess their needs; assist in selecting an appropriate wheelchair; receive information and training in the use and maintenance of their wheelchair; and ongoing support, follow up and referral to other services where appropriate (World Health Organization, 2023). These initiatives have included the creation of training resources (World Health Organization, 2012a, 2013) and flexible learning methodologies (Burrola-Mendez et al., 2018), aiming to foster a skilled workforce. More recently, the focus has shifted towards developing a sustainable training approach within university rehabilitation programs. This transition comes in response to the recognition that wheelchair-related education in curricula is insufficient (K. H. Fung et al., 2017) and that educators face several barriers in integrating wheelchair content into their programs (K. Fung et al., 2019). This situation has led to insufficient training and limited competency of entry-to-practice rehabilitation professionals in wheelchair service provision (Toro-Hernández et al., 2019, 2020).

In response to this challenge, the International Society of Wheelchair Professionals (ISWP) developed the Seating and Mobility Academic Resource Toolkit (SMART) using a participatory action research approach (PAR) (Rushton et al., 2020). The SMART was an open-access website where educators could share and access various resources developed by peers, including PowerPoint presentations, course syllabi, lab guides, case studies, and online modules (Rushton et al., 2020). The response from the wheelchair sector was highly positive, with 22,000 unique users recorded from the website’s launch in May 2018 to its closure in August 2022.

While the SMART initiative enhanced access to wheelchair-related teaching resources, it did not address other significant challenges faced by educators. These challenges include the lack of awareness regarding the need to integrate wheelchair content into curricula, the limited knowledge of efficient pedagogic approaches for the integration of wheelchair-related content, and the lack of guidelines and resources on how to integrate wheelchair content into curricula (K. Fung et al., 2019; K. H. Fung et al., 2017; Rushton et al., 2020). In 2020, ISWP obtained a USAID grant to develop the Wheelchair Educators’ Package, WEP, (https://wep.iswp.org/) an online resource to inform wheelchair-related education within academic programs.

PAR is a collaborative, iterative, action-driven and often unpredictable approach aimed at addressing social issues experienced by a community (Baum et al., 2006; Cornish et al., 2023). This approach emphasizes the importance of building relationships with individuals experiencing social issues and fostering collaboration between all types of actors (e.g., end-users, community members) and researchers. The objective is to co-create knowledge and promote social change (Bradbury, 2015; Cornish et al., 2023; Kindon et al., 2007; Vaughn & Jacquez, 2020). The PAR approach prioritizes the development and use of methods that empower participants to act as collaborative partners in the research process. This involves shared decision-making to increase the likelihood that outcomes of the research are relevant and can effectively translate into real-world impact (Cornish et al., 2023; Vaughn et al., 2018). Partner level of engagement is considered a continuum that can range from inform (e.g., researchers provide information to the community) to empower (e.g., the community leads research decision making).

The purpose of this study was to describe and measure use of the PAR approach to develop the WEP. We also share reflections and lessons learned from using a PAR approach, with the intention of assisting future researchers in applying PAR approaches.

Methods

Design

In this paper, we report on our use of a 10-step PAR process (Tandon, 2002) in conjunction with the Participation Choice Points in the Research Process Model (Vaughn & Jacquez, 2020). The 10-steps of PAR include: (step 1) identify actors, (step 2) joint agreements between researchers and actors, (step 3) small group responsible for research cycle, (step 4) joint design of research, (step 5) joint data collection, (step 6) joint data analysis, (step 7) sharing with actors in the problem situation, (steps 8 and 9) development and implementation of change plans, and (step 10) consolidation of learning. While the 10 steps are presented in sequence in this paper for ease of read, it is important to note that a participatory process is cyclical and iterative among the 10 steps.

The Participation Choice Points encompass five levels including: inform (information is provided to the community), consult (input is obtained from the community), involve (researchers work directly with the community), collaborate (the community is a partner in the research process) and empower (the community leads research decision making) (Vaughn & Jacquez, 2020).

We will describe how these guiding frameworks were used in conjunction with tools and processes to facilitate varying levels of participation according to our actors’ needs and preferences, while also considering pragmatic factors and core components of PAR. The study was verified exempt by Belmont University Institutional Review Board (#950).

PAR Process and Levels of Participation

Step 1: Identify actors (Inform)

In April of 2020, we formed a WEP Steering Committee composed of six ISWP representatives who had led several wheelchair-related projects and initiatives that provided the foundation for the current project (Burrola-Mendez et al., 2023; K. Fung et al., 2019; K. H. Fung et al., 2017; Rushton et al., 2020). To reach a diverse group who could contribute to the development of a WEP that would be of use to educators in diverse contexts across the globe, the Steering Committee developed a Request for Expressions of Interest that outlined project and support team details, as well as Development Team responsibilities, composition, timeline, work effort and compensation. It was used to facilitate an open call for the WEP Development Team advertised through the ISWP and World Health Organization (WHO) Global Cooperation on Assistive Technology member listservs and other ISWP social media channels between April 22 - May 11, 2020. We received a total of 71 responses by our deadline and subsequently created a 32-member short-list based on the WHO Handbook for Guideline Development composition criteria (World Health Organization, 2012b). Specifically, we selected a team that encompassed members representing technical experts (e.g., wheelchair provision, wheelchair provision education, package/program development, curriculum development), end-users (e.g., university-based faculty members, community-based educators), experts in assessing evidence (e.g., scoping review) and representatives of groups who would be affected by the Package (e.g., health care professional students and wheelchair users) who also represented a cross-section of professions (e.g., occupational therapy, physical therapy, prosthetics and orthotics, medicine and nursing) and diverse settings (e.g., low-, middle- and high-resourced settings). Our Development Team (including the Steering Committee) represented 21 countries, 16 languages and 9 professions. The WEP team sociodemographic characteristics are provided in Table 1. The intended level of participation of this step was Inform as the high-level project details were dictated by pragmatic factors, including funder requirements.

Step 2: Joint Agreements between Researchers and Actors (Consult / Involve)

Within the context of our project, there were imposed and consensus-driven agreements. The imposed agreements were established by the Steering Committee to facilitate adherence to our timeline and deliverables according to the funder. For instance, the project timeline (i.e., start/end dates) and WEP Development Team member work effort (i.e., Year 1: 12-16 hours/month; Year 2: 6-8 hours/month) were designated in advance and it was required that each member agree prior to engaging in the project. Of note, except for the Steering Committee members, all work was non-commissioned and thus volunteer hours. The consensus-driven agreements mainly included the collaborative development of our team Rules of Engagement, Roles and Responsibilities, and Publication and Presentation Policy. In terms of Rules of Engagement, there were 3 categories: shared commitment (e.g., active participation, collaborative spirit, transparency, responsibility); eliciting and sharing ideas (e.g., active listening, share ideas/thoughts/concerns freely, ask for clarifications, speak slowly); and embrace diversity (e.g., respect for differences, acknowledge the diversity within the group, embrace context-specific experiences, empathy with different situations and contexts). The Roles and Responsibilities document outlined the specifics for each category of WEP Development Team member, including SC member, SC member in support of a Working Group (WG), WG Lead, and WG Member. It described that all WG members must attend at least 50% of all WG meetings to which they belong. The Publication and Presentation Policy outlined the minimum requirements for authorship and acknowledgements, as well as project-specific requirements for both publications and presentations. While the Rules of Engagement were generated entirely by the Team, the Roles and Responsibilities and Publication and Presentation Policy were initially generated by the Steering Committee and subsequently revised according to feedback from the Team. All three consensus-driven agreements were used consistently by each WG throughout the entire project process and aided with decision-making along the way. The intended level of participation at Step 2 was Consult for the imposed agreements and Involve for the consensus-driven agreements.

Step 3: Small Group Responsible for Research Cycle (Involve)

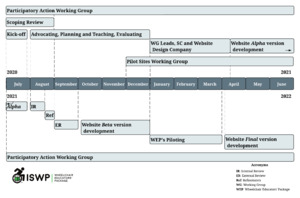

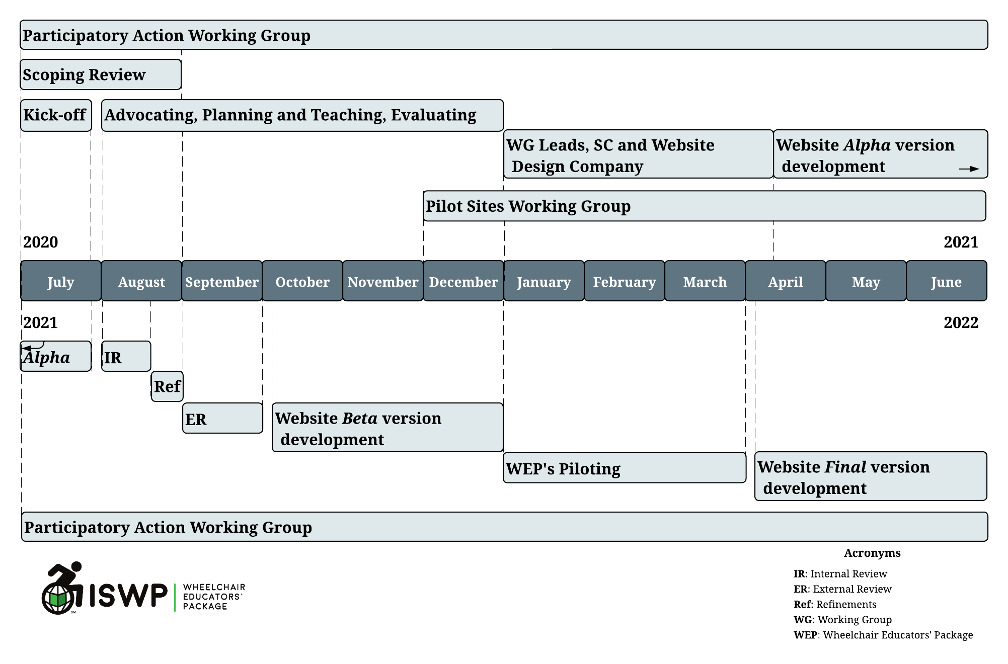

Figure 1 presents the WEP development team organizational structure (left side of figure), highlighting that the Steering Committee supported the WEP Development Team in its entirety, including six WGs, each with a WG Leader. Each member of the Team self-selected 1-2 WGs with which to engage for the duration of the project. Table 2 presents the scope and objectives established by each WG that outline the components of the project for which each WG was responsible. The tasks and the timeframe for completion of required tasks varied according to the WG. Figure 2 depicts the 2-year project timeline and tasks. Involve was the intended level of participation for Step 3.

Step 4: Joint Design of Research (Collaborate)

To secure project funding, an initial research protocol was developed by the Steering Committee. This protocol was used to provide a brief synopsis of the project in the Request for Expressions of Interest in Step 1 and then presented in its entirety at the project kick-off meeting. During the kick-off meeting, the WEP development team were offered the opportunity to provide input into the overarching project purpose, scope, and WEP target audience, resulting in minor refinements. Each WG subsequently developed the more targeted scope and objectives for which they would be responsible to contribute to the overarching project objective (as described in Step 3 and presented in Table 2). The team was also invited to contribute to the design of the WEP logo (Figure 3) which was facilitated by our web design company. Refinement of the overarching project purpose, scope, and target audience, development of the WG-specific scope and objectives, as well as the opportunity to contribute to the design of the WEP logo supported a sense of belonging for team members and facilitated participation at the Collaborate level.

Step 5: Joint Data Collection (Collaborate and Empower)

Each WG contributed to data collection according to their scope and objectives. Specifically, the PAR WG developed the procedures (e.g., survey development and roll-out guidelines) and tools (e.g., surveys to assess engagement, experiences, and satisfaction as described in the Measurement of PAR Approach section below) to collect data from the WEP development team to assess process and inform changes throughout the project to facilitate optimal participation by all members. The Scoping Review WG conducted and published a review synthesizing the literature on wheelchair service provision education to inform WEP content development (Burrola-Mendez et al., 2023). The Advocating, Planning & Teaching, and Evaluating WGs each collected, developed, and organized resources for the WEP, liaising with the website development company throughout the process to structure the website. The website design considered user-centered strategies, simplified navigation, usability accessibility standards and low bandwidth requirements (Government, 2022; Lee & Kozar, 2012). The Pilot Sites WG established the methods (e.g., mixed methods) and tools (e.g., surveys and focus groups) for evaluating the usability of the WEP via internal and external review of the alpha version and ultimately piloting the beta version. In addition to developing the methods and tools, each WG also collected the data. Support for development of methods, tools, and data collection was provided by the WG Lead and Steering Committee, including instruction and education as needed. This step afforded WG members a Collaborate or Empower level of participation, according to their desired level.

Step 6: Joint Data Analysis (Collaborate and Empower)

As with joint data collection, each WG contributed to data analysis according to their scope and objectives. In contrast to data collection, fewer WG members participated in the data analysis as their skills, interest, and time available required for this step were less. For the most part, WG members were content with having WG Leads analyze and present the data to the WG for interpretation and discussion. This was the case with all survey data. However, there was more interest in analyzing the qualitative focus group data within the PAR and Pilot Sites WGs with several members engaging in the process. For both quantitative (survey) and qualitative (focus group) data, WG Leads offered to provide WG members with education and support regarding the data analysis. This offer was accepted for the qualitative but not the quantitative data and we honored the varying levels of participation according to the preferences of our WG members. As with Step 5, Step 6 afforded WG members a Collaborate or Empower level of participation, according to their desired level.

Step 7: Sharing with Actors in the Problem Situation (Empower)

Internally, the WEP development team shared project information using a structured format. Specifically, the entire WEP development team met 2-3x/year, the Steering Committee 1x/week, combined WG Leads and Steering Committee 1x/month, and the WGs 1x/month. Although this frequency did vary throughout the project depending on need and project stage, this frequency represented the target. The meeting times fluctuated to accommodate as much as possible the different time zones of WEP development team members. Each meeting was conducted via Zoom, had an agenda, a PowerPoint presentation, was video recorded, and minutes were provided that included the recording link within 1-week post-meeting. Following feedback received regarding the challenge following all meeting details of members whose maternal language was not English, the meetings were sometimes followed up with a video describing post-meeting offline work instructions. These videos were recorded in several languages (i.e., English, French, Spanish, and Italian) to accommodate members’ needs. In essence, the variety of forms of auditory and visual communication shared via meeting discussions, PowerPoint presentations, and videos were intended to enhance accessibility given the different languages represented by the team members. Externally, the WEP development team also shared project information throughout and at the end of the project via project reports to our funder, conference presentations and workshops (i.e., International Seating Symposium, Oceania Seating Symposium, Latin American Seating Symposium, European Seating Symposium, World Federation of Occupational Therapists International Congress, International Society of Prosthetics and Orthotics Global Partnership Exchange, Congrès de l’Acfas, and the International Conference on Digital Inclusion, Assistive Technology, and Accessibility) and WEP launch webinars in English, French, Spanish, Swedish, Italian, and Hebrew. All WEP development team members were also encouraged to share project information at local meetings and conferences and were supported as needed to do so. Many WEP development team members engaged in sharing the project information and acquiring feedback regarding the WEP both internally and externally and were thus participating at a Collaborate or Empower level.

Steps 8 and 9: Development and Implementation of Change Plans (Empower)

Given that the WEP was developed as a resource for educators in different health care profession programs worldwide, the intention was that its development, launch, and informational webinars would facilitate a change (i.e., improvement) in wheelchair service provision education. How the WEP may be implemented, and its use evaluated to improve education will differ depending on the university program itself and the context within which it is situated. This resource in and of itself facilitates participation at the Empower level for educators worldwide to advocate, plan and teach, and evaluate the wheelchair service provision education offered within their respective institutions. As the WEP is a living resource, the intention is that it will be updated over time with the latest evidence and resources, including those shared by educators themselves, as a means of minimizing the barriers faced by educators in integrating wheelchair content into curricula.

Step 10: Consolidation of Learning (Empower)

This project offered opportunities for reflection and consolidation of learning throughout the 2-year timespan. Specific to our PAR approach itself, the data collected and analyzed by the PAR WG facilitated a process of reflection and refinement to PAR processes. The consolidation of learning from that perspective, the focus of this paper, was a key component of this project the results of which we share here with the goal of informing others who plan to engage in a project of this nature. The lessons learned are highlighted in the Reflections section. Other opportunities for consolidation of learning included learnings about different types of data collection and analysis, wheelchair service provision education content itself, as well as organization of our project findings into reports, presentations, workshops, and instructional webinars.

Measurement of the PAR approach

The PAR WG developed the following assessment tools to evaluate member’s engagement, experiences, and levels of satisfaction in the integration of PAR approaches.

Engagement

WG meeting attendance was monitored throughout the project. The data was captured in an Excel Worksheet monthly and monitored quarterly.

The Levels of Engagement Questionnaire assessed members’ satisfaction in their perceived Participation Choice Points (i.e., inform, consult, involve, collaborate, empower) (Vaughn & Jacquez, 2020) across the 10-Step PAR process (Tandon, 2002). Members were prompted to select their participation choice at each step of the PAR process and rank their satisfaction using a 5-point Likert response scale (i.e., 1=not at all satisfied; 2=slightly satisfied; 3= moderately satisfied; 4=quite satisfied; 5= extremely satisfied). Members received the Participation Choice Points definitions and the summary of the characteristics of each step PAR process as supplemental material to complete the survey. The questionnaire was distributed among WEP development group members at the endpoint.

Experiences, challenges, and levels of satisfaction

The 28-item WEP Experiences Questionnaire explored experiences, workload, barriers, strengths, and weaknesses with the project processes. The Experiences section included 4 sub-sections (i.e., time, communication, COVID-19, and overall experience) and used a 5-point Likert response scale (i.e., 1=strongly disagree; 2=disagree; 3=not sure; 4=agree; 5=strongly agree). The Workload included two questions about participants’ work effort in the project. The last section, Barriers, Strengths, and Weaknesses was composed of open-ended questions. The questionnaire was distributed among WEP development group members at two timepoints (midpoint and endpoint).

PAR approach process

The 8-item PAR Components Integration Questionnaire evaluated the perceived level of importance and the satisfaction with the integration of four PAR components (i.e., mutual respect, significant engagement of partners from various contexts, sharing knowledge, and transparency) in the project. The survey used a 5-point Likert response scale (i.e., 1=not at all important/satisfied; 2=slightly important/satisfied; 3= moderately important/satisfied; 4=quite important/satisfied; 5= extremely important/satisfied). The questionnaire was distributed among WEP development group members at the endpoint.

The Adherence to the Rules of Engagement Questionnaire explored members’ observance to the group’s established guidelines to elicit and share ideas, share commitment, and embrace diversity. The descriptors of each component were established by members during the kick-off meeting. In total, the group agreed on 20 rules that were assessed using a 5-point Likert type scale (1= never adhered to; 2= rarely adhered to; 3= sometimes adhered to; 4= often adhered to; 5= always adhered to). The questionnaire was distributed among WEP development group members at the endpoint.

Data analysis

The iterative nature of the PAR processes allowed us to continually gather and analyze feedback. The measurements described encompassed quantitative and qualitative data, which was analyzed to attain the broadest understanding of the WEP members’ experiences using a PAR approach. Means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables (or non-parametric equivalents) were calculated to describe and summarize the quantitative data. The qualitative data were analyzed using content analysis and organized by themes. Visual representations of the data included horizontal graphs, stacked bar chart and side-by-side joint displays. This latter presentation is a type of visual that juxtaposes quantitative and qualitative results next to each other to facilitate comparison (Guetterman et al., 2021) and help to qualitatively explain the quantitative data.

Results

Engagement

Table 3 provides a comprehensive overview of the project meetings and volunteer participation. Over the course of the 2-year project, a total of 126 meetings were conducted, which represented 1169 person-hours, with 77.9% of these hours contributed by volunteers. The SC met the most with 52 meetings throughout the project and WGs’ had a total number of meetings that ranged from 6 to 20. The Scoping Review and the Evaluating WGs held the fewest meetings, while the PAR WG led the pack with the highest meeting frequency. Attendance rates across the WGs varied, ranging from 55.3% to 81.9%. Similarly, the representation of volunteers in these meetings varied from 57.13% to 81.65%.

A total of 19 members (59%) responded to the Levels of Engagement Questionnaire at the end of the project. Figure 4 depicts the frequency of responses in participant’s perceived level of participation according to the participation choice points and satisfaction with their level of participation across the 10-step PAR process. Overall, participants indicated a generally high level of satisfaction with their perceived level of participation throughout the project. Most responses fell within the categories of “extremely satisfied” and “quite satisfied”. Notably, more participants expressed higher levels of satisfaction when their participation choices were “collaboration” and “empowerment” across different steps. For instance, responses in steps 1,4,5,6, and 8 indicated strong levels of satisfaction in their collaborative efforts with these steps of the PAR process. Similarly, participants indicated satisfaction with an “empower” role in steps 3, 7, and 10. No participant reported feeling “not at all satisfied” with their choice of participation during the project. Interestingly, there were discrepancies between our intended levels of participation across the steps and the participants’ perceived level of participation. In some steps, most participants felt they participated more (e.g., Step 1) or less (e.g., Step 9) than our intended level, while in other steps the perceived levels of participations were distributed across the levels.

Experiences, challenges, and levels of satisfaction

A total of 19 members (59%) responded to the WEP Experiences Questionnaire in 2021 and 2022. Since the questionnaire did not force responses, some questions were skipped, resulting in fewer answers.

Experiences

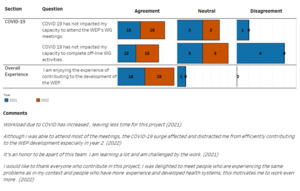

Figures 5 and 6, show that most members responded in agreement with the questionnaire statements that described the organization of the project in terms of time and communication, with some small improvements observed between the first and second year of the project. Figure 7 demonstrates that for the most part COVID-19 did not impact the members capacity to contribute to the project and that all members enjoyed the experience of contributing to the development of the WEP.

Workload

In the first year, over three-quarters (79%) of participants reported that the workload was manageable, yet slightly more than half (52%) acknowledged contributing more hours than initially anticipated to the project each month. In contrast, in the second year, the majority of members (95%) found the workload manageable, with less than half of them (42%) indicating that they exceeded the expected monthly contribution of hours to the project.

Barriers, strengths, and weaknesses

Participants faced some contextual barriers, such as issues with internet connection and meeting times, which hindered their participation in WEP activities. Suggestions for improvement included more engaging activities and communication during the second year. In terms of strengths, participants praised the use of multiple modes of communication, the project’s organization and leadership, and the opportunity to connect with actors globally (Table 4).

PAR approach process

A total of 17 members (53%) completed the PAR Components Integration Questionnaire (Figure 8). Overall, members deemed all PAR components to be important and expressed high satisfaction with their integration in the project. No responses were received from the two less positive rankings of the scale (i.e., slightly important/satisfied and not at all important).

The Adherence to the Rules of Engagement Questionnaire was completed by 20 members, representing 62.5% of the total participants (Figure 9). The results indicated an overall high level of adherence across the three assessed areas: eliciting and sharing ideas, embracing diversity, and shared commitment. In the areas Embrace diversity and Shared commitment, members reported the highest levels of adherence. However, in the area of Eliciting and sharing ideas members reported slightly lower adherence to the rules. For example, four members mentioned rarely adhering to the rule “Raise hand to speak”, and one member reported never adhering to the rule “Avoid or spell acronyms”.

Reflections on the use of a PAR approach

At the core of PAR lies the establishment of collaborative relationships interested in generating knowledge-for-action to promote social change (Cornish et al., 2023). We built a community of global actors from various geographical, political, and health care systems interested in improving wheelchair service education globally. Over a 2-year period, our group, consisting of 32 actors from 21 countries, brought their local knowledge, experience, expertise, and heritage to co-develop the WEP. The fact that only one member of our group withdrew during the 2-year project highlights both the commitment of our members, as well as the effectiveness and appreciation of our PAR processes.

While PAR offered a powerful path to collaborative engagement, it was not without challenges. Working across continents, our team of 84% volunteers encountered challenges juggling time zones and respecting diverse schedules (Figure 5), as well as ensuring our communication was clear considering the variety of languages (Figure 6). The challenges were intensified by the global context, especially with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, some group members experienced difficulties attending meetings and completing tasks due to COVID-19, particularly in the first year of the project (Figure 7). Aligned with the PAR approach, we remained flexible and employed creative adaptability to address the challenges that were identified through our questionnaire results. For example, we added a communication strategy (i.e., post working group meeting short videos with succinct instructions for completing off-line activities in a variety of languages) to improve member’s understanding of instructions and thus capacity to complete requested tasks. Our questionnaire results provided evidence of the usefulness of this strategy and thus, although it was an unanticipated workload, the development of these videos was ultimately a good use of our time and resources. We prioritized our strategies to address challenges based on those that we felt would make the most impact with the resources available. That meeting attendance was on average 78% (Table 3) across the different groups, over the two-year period, demonstrates the effectiveness of our PAR approach and strategies for addressing feedback.

Beyond sheer attendance, members’ level of engagement across the participation choice points trended towards collaborate and empower (Figure 4) even for those steps of the PAR process for which we intended a less engaged level of participation due to pragmatic factors. We suspect that our members’ high levels of participation and feelings of engagement were a by-product of both their commitment to the project based on the global need for improved wheelchair service provision education, as well as our overarching philosophy of collaboration regardless of pragmatic factors which we accomplished in part through our consensus-driven processes, such as the Rules of Engagement. In instances where the levels of participation were lower than expected or desired, a variety of factors may have contributed such as member’s knowledge (e.g., Step 6: Joint Data Analysis) or interest (e.g., Step 7: Sharing with Actors in the Problem Situation, particular sharing outside of the WEP Development Group). We believe that our efforts to provide education or support facilitated members’ engagement to their chosen level of optimal participation.

PAR thrives on iteration and collaborative active engagement. To adapt and address challenges to facilitate desired optimal participation from all team members often requires much more time than originally anticipated. Team members dedicate many volunteer hours based on commitment to social change. We urge funding agencies to acknowledge the inherent time needs of this approach. Flexibility in grant timelines must be a priority to nurture successful collaboration and accommodate team member’s schedules and resultant capacity to participate. This need was emphasized through member’s comments provided via questionnaires, such as "Sometimes there’s a time pressure involved in completing the offline work. I think that we need to be given a more realistic time frame to complete certain tasks, considering that we are doing this around our full-time work responsibilities." (Table 4). Furthermore, ensuring equity in research relationships involves compensating all members of the research process (Black et al., 2013). Our group was comprised of 84% volunteers who did not receive any form of compensation for their unique contributions to this research partnership. The sheer volume of work contributed by volunteers, as shown in Table 3 (and likely underestimated, considering unreported offline efforts), underscores the need for fair compensation. Moving forward, a funding landscape that values time and respects volunteers is needed to embrace the transformative power of participatory research.

We accomplished our objective of developing the WEP using a PAR approach and learned valuable lessons along the way. First, to conduct a project using a PAR approach requires at least double the amount of time than if a PAR approach was not used (e.g., to provide support and education to members as needed and develop strategies to address challenges articulated by members). However, it was time well spent given that the result is a WEP that is useful worldwide. Second, measurement of the PAR approach throughout the project, while also time consuming, was important to identify challenges preventing optimal participation. In this project, we developed the measures during the project. Our process may have been more efficient had we developed the measures (at least an initial versions) in advance. Third, securing compensation for all team members is important and may have resulted in a more efficient process.

Conclusion

This paper explored the empowering journey of employing PAR in the development of the WEP. Through the lens of type and level of participation, the analysis of feedback from the PAR working group revealed a process not only iterative and insightful, but also profoundly empowering. Transdisciplinary research and product development, often fraught with complexities, thrived under the collaborative and inclusive space fostered by PAR.

While recognizing the potential of PAR, we acknowledge the importance of transparent communication, ensuring every member understands their role and commitment throughout the project’s lifecycle. This fosters ownership and strengthens the fabric of global partnerships.

Beyond our reflections, this work offers a tangible example of how academic and global partners can co-create an environment that empowers participants, especially volunteers. WEP team members’ voices, knowledge, and commitment are not simply heard, but actively woven into the project, leading to more inclusive and potentially impactful outcomes. Moving forward, the WEP stands as a testament to the transformative power of PAR. The success of its development compels us to embrace this participatory approach wholeheartedly, recognizing its potential to ignite positive social change and empower communities.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank members of the WEP Development Group, Amira Tawashy, Deb Wilson, Diane Bell, Dietlind Gretschel, Ed Giesbrecht, Ferdiliza Dandah Garcia, Freddy Alfonso, Herath Pathirannahalage Uthpala Mihiran, Jessica Presperin Pedersen, Karma Phuentsho, Kofo Davies-Otto, Lori Rosenberg, Marco Tofani, Marie Abou Saab, Meredith Hope Lee, Patience Mutiti, Phatcharaporn Kongkerd, R. Lee Kirby, Rosemary Joan Gowran, Silvana Contepomi, Suresh Kamalakannan, Taylor Bumbalough, Thais Pousada, Tomasz Tasiemski, for their contributions to the development of the WEP; and members of ISWP, Jon Pearlman, Krithika Kandavel, and Nancy Augustine for their administrative support.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)